Polite (2023 October 15th)

[This is a story that’s been four years in the making. I no longer remember all the details exactly, so I’ve taken some poetic license here and there. Just so you know that this isn’t up to my usual standards..]

Background

So, picture this. It’s Dublin and I’m in 2019, at Worldcon, which in this city doesn’t have a clever name, just "Dublin 2019: An Irish Worldcon". Although I had intended to go with my parents, my father had an unfortunately-timed accident that fractured his clavicle, meaning my parents were staying home, and with my relationship with RL being on its last legs, I come by myself, although Todd and Tracy are there with some of their family. The Airbnb that I had booked got cancelled, and I had scrambled to find another one, which I did in a mediocre studio that was clearly designed for this kind of short-term rental. It is a lonely time.

The convention has its charms, some of which I don’t expect — Jeanette Ng’s [ed: confirm name/spelling] speech at the Hugos is a highlight, as is an incredible panel about African SF, which starts with a gentleman delivering a magnificent rant about how one of the panelists couldn’t attend, because the Irish government wouldn’t give them a visa, and how the visa for Ireland is in some way controlled by the British government, and how this is just one more demonstration of the presence of colonialism in today’s world, before the panelists deliver recommendation after recommendation of work that I’ve never even heard of. After a few minutes I realize there will be more than I can fit in my head and I spend the remainder of the hour scribbling frantically into my phone.

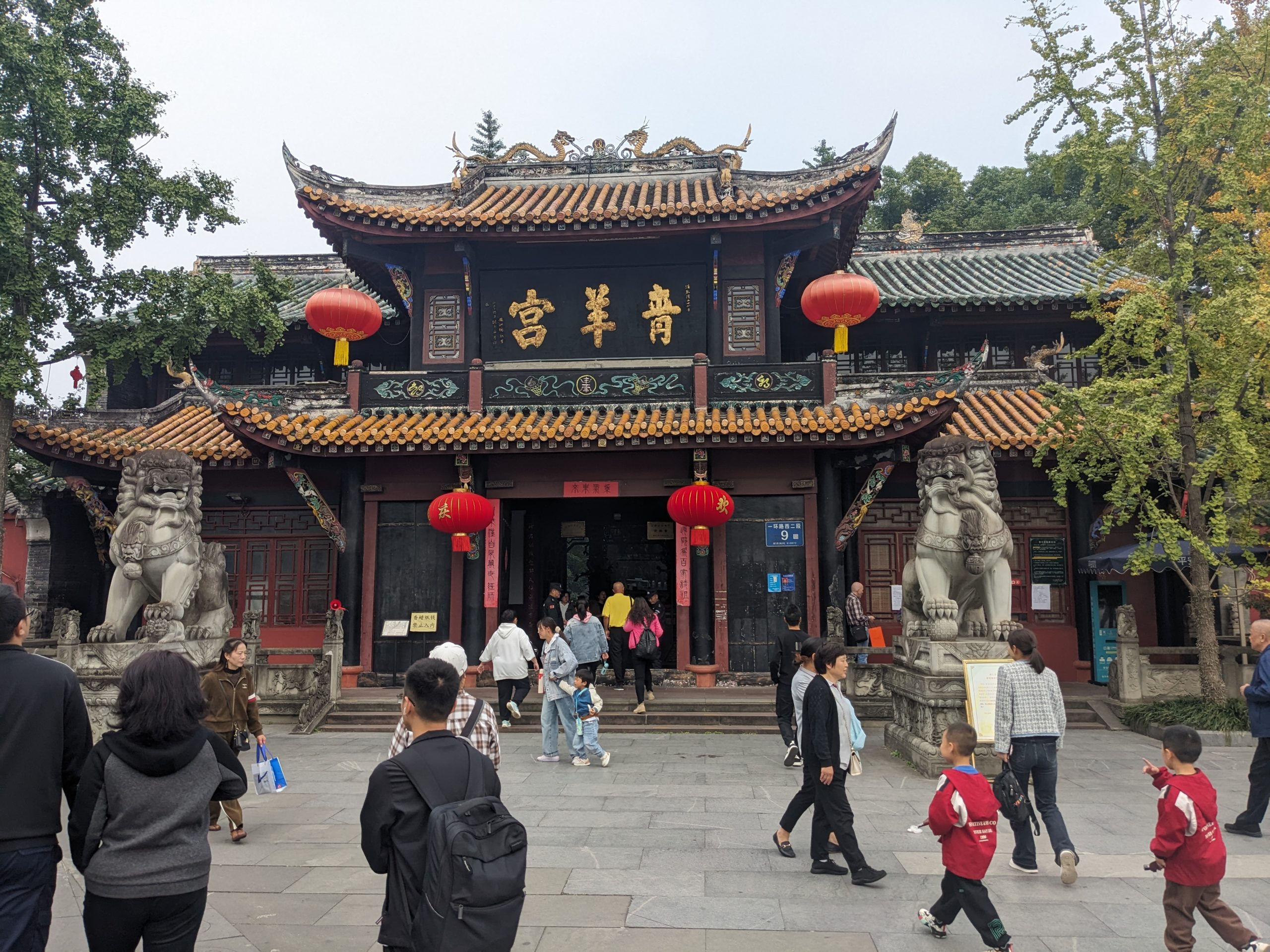

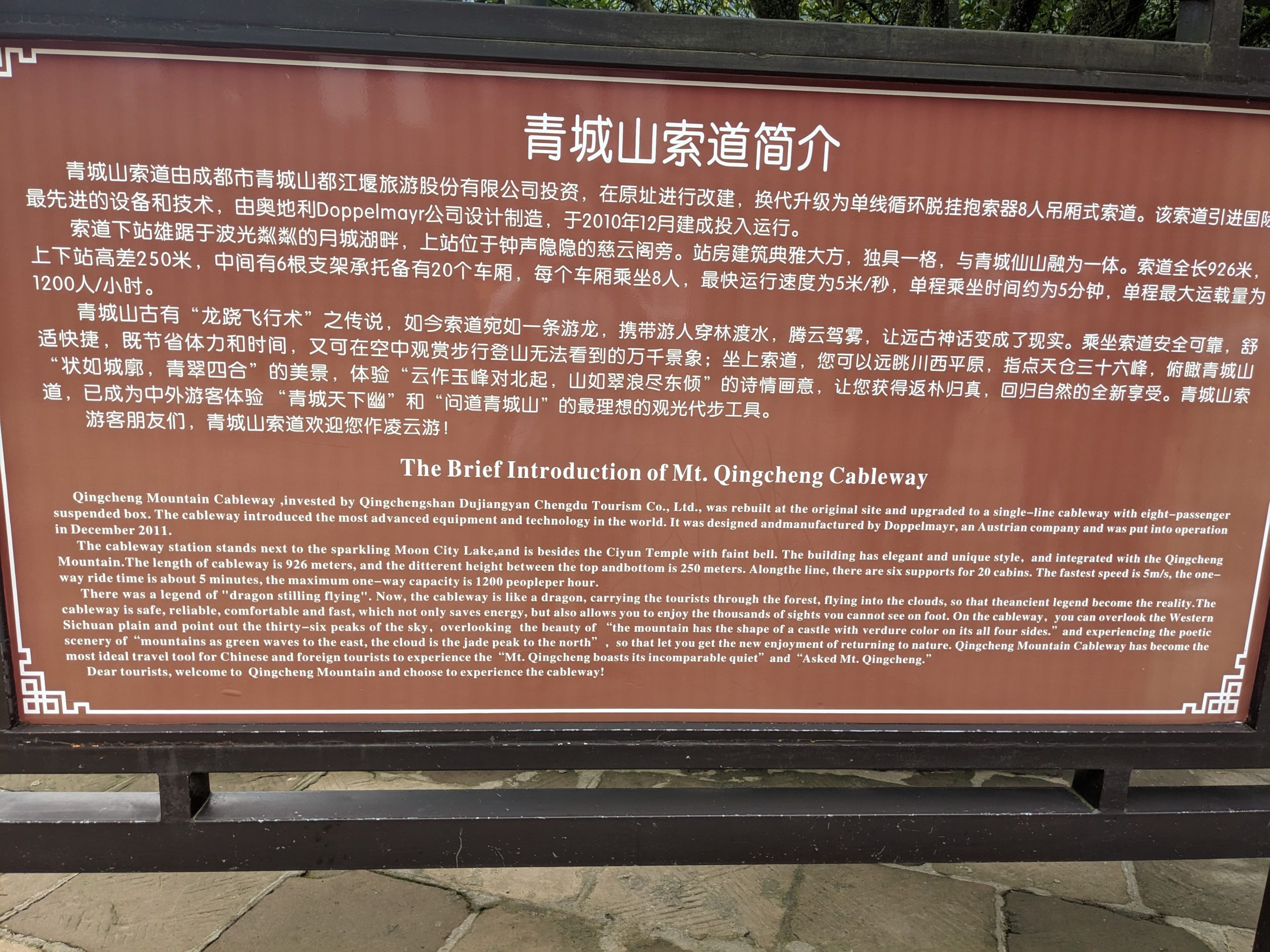

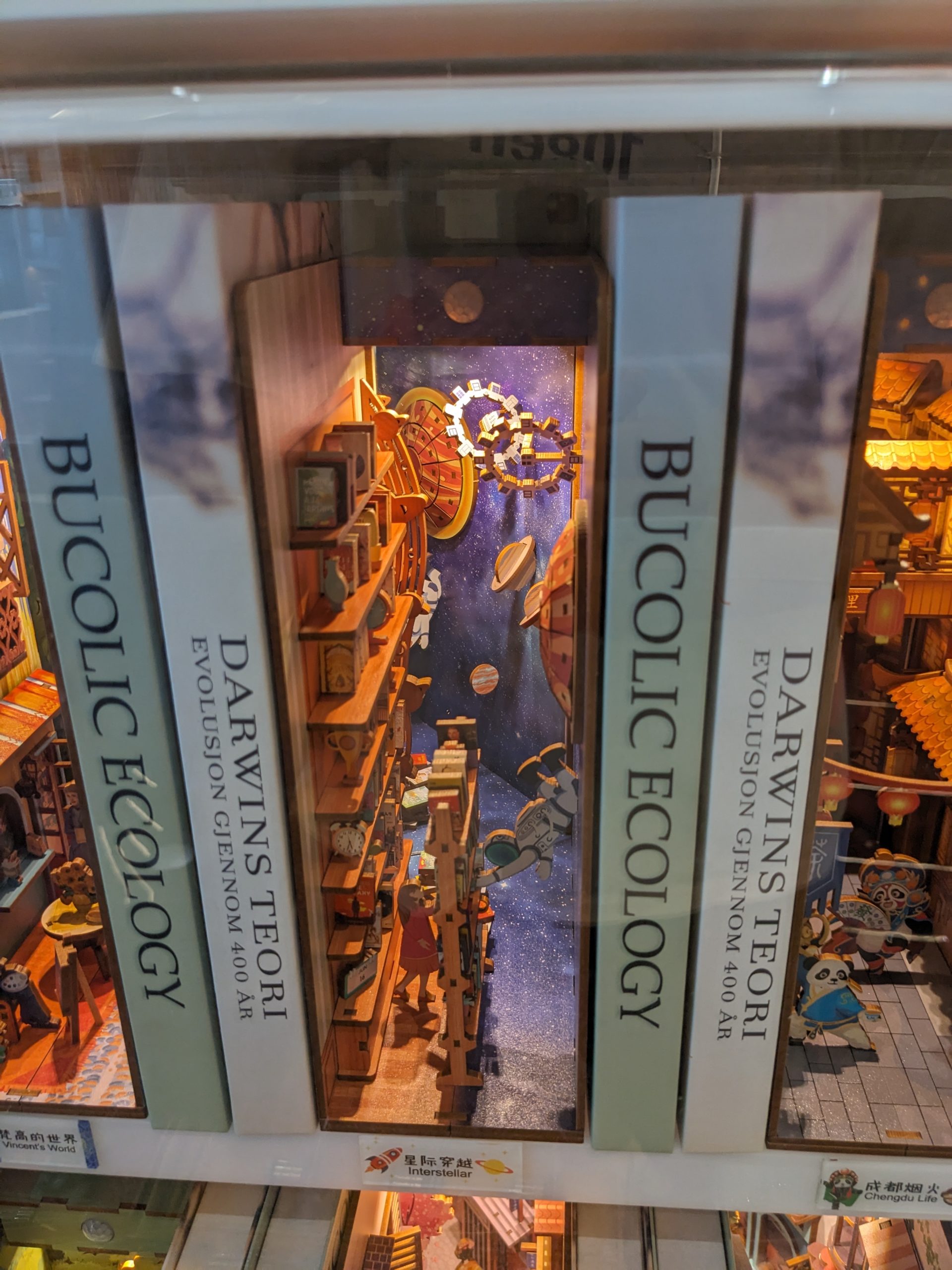

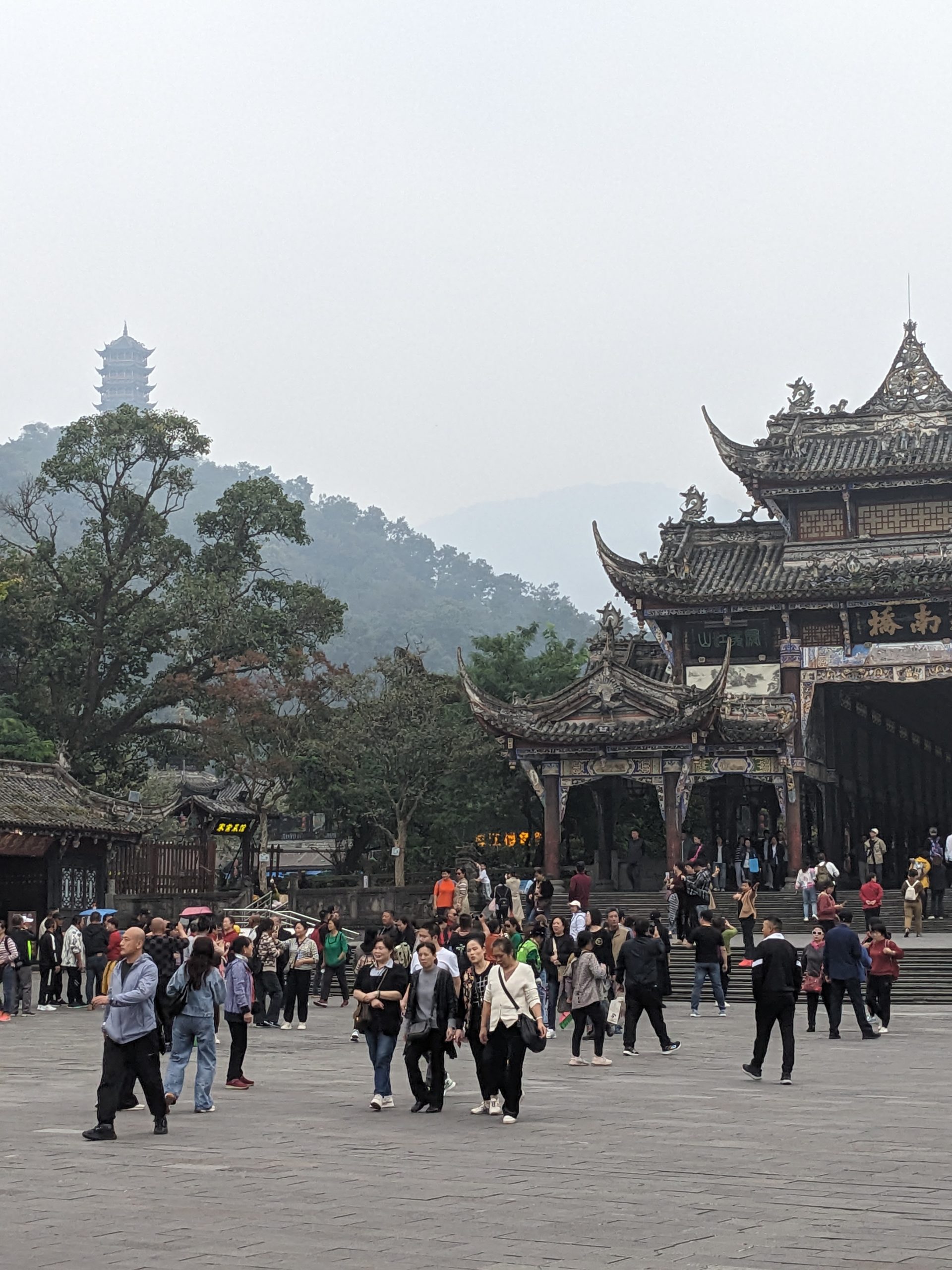

The exhibition hall is another highlight. Not only is there a DeLorean parked in the middle of it — a piece of Irish science fiction right there! — but there are tables from many different places. I pick up a book of some kind of Scandinavian micro-stories in translation, and a book containing academic analysis of African science fiction. There are also tables for the upcoming bids — we are voting for 2021, with DC running [ed: who else?], but Nice is bidding for 2023, and so is some city in China. They are generous with the swag; I get a pin which reads "Chengdu: More Than Panda".

It feels very much like a "World" con, which makes an interesting change of pace from the feel of most conventions, which are increasingly attended by the old white fogeys that my parents’ generation of fans have become. At a bid party for CoNZealand (who have already won 2020), I meet a gentleman from Norway. This is the first convention I’ve been to where there is a bar. (I spend a pleasant time watching the Gaelic football game on a projector with a bunch of fans who understand how the game works better than I do.

Still, I’m somehow disaffected. I spend a certain amount of time riding the escalator from level to level, not sure what to do, not knowing anyone and not totally convinced it’s worth the effort to try. At some point, I have an epiphany, that while this convention satisfies an important part of me — the part who is a science fiction fan, who attends conventions recreationally, who cares about what it means to be a nerd — it hasn’t been as nourishing for the other parts, such as the New Yorker, the chiptune partisan, the one who served in Peace Corps, the one who thinks in software architecture. I become aware that I am at the junction of several different facets, and become aware how rare it is to connect, to be embraced on more than one of them. (Sometimes even one is hard.)

Skip ahead a couple years. Of course I don’t attend CoNZealand, even remotely. DisCon is relocated to the end of 2021, and I attend with my family since it’s reachable by car. It’s a quiet convention, more typically American in flavor. The "World" part of "Worldcon" is absent; it’s more like the "World Series". By this point, Nice has dropped out of bidding for 2023; the last bids remaining are Chengdu and (of all places) Winnipeg. The rumor mill is full of intrigue about the Chinese bid. Jeddah’s bid [ed: when did this happen?] was soundly rebuffed, and there’s some concern that traveling to China means supporting an Evil Empire full of human rights violations. Not only that, something seems to be up with the voting; mailed-in ballots are arriving that are incompletely filled out, often without the mailing address filled in. There’s speculation that the Chinese government is funding the bid, perhaps only to demonstrate some soft power, but perhaps to do something nefarious like taking over our good, red-blooded Worldcon. After all, the cost of a few thousand Worldcon voting memberships is nothing to the government of a billion people. The other perspective, that Chengdu is home to its own science fiction community including the most popular science fiction magazine in the world, doesn’t get as much discussion. Neither does the idea that if I were a citizen of another country and could have Worldcon at my doorstep simply by voting for it, I would do so in a heartbeat. I wouldn’t say that everyone is suspicious of the Chinese, but there’s a xenophobic undercurrent to the discussion which is surprising in a community which prides itself on being open-minded and welcoming.

The Chinese fans, for their part, don’t seem prepared to address the concerns of the Americans. There’s a Q&A panel, where the dueling bids are asked questions by an audience. One question goes something like "Since free expression is such an important part of science fiction, how will the Chengdu bid provide an environment where one can speak without worrying about offending the Chinese government? For example, how can something like Jeanette Ng’s Hugo speech happen in an environment of censorship and repression?" The answer, once translated from Chinese, is something along the lines of, of course there is censorship in China and the bid cannot contravene government policy, but that they expect people to be able to have the discussions they want. On the other side, the Winnipeg bid has its own issue: they have an uphill battle trying to convince me that a plains town in the middle of Canada would be worth visiting.

I don’t even remember who I vote for (maybe a write-in protest vote?), but Chengdu wins by a large margin. The on-site attendees mostly break for Winnipeg, but the mail-in votes are largely for Chengdu and they outnumber the on-site ones handily.

I’ve never been to China — I had planned an ill-fated trip for early 2020 with some friends. What even would a Chinese Worldcon be like? It could be much the same, with the same graybeards attending, an insular event for tourists at a fancy location. But there’s a chance it would at least be different, a chance for it to be more like the Dublin Worldcon, a chance for the "World" in the name to mean something. This would be the first time China hosts, and only the third time Worldcon takes place in a non-English-speaking country (the other two were The Hague and Tokyo). It could be that a Chinese Worldcon would be something dramatically different, that the Chinese approach to the event would be foreign in some compelling way. I attend a bid party to try to check it out. To my disappointment, it’s largely the same as every other bid party I’ve ever been to, with veggie trays from a local supermarket. I’m convinced that the greybeards don’t have to worry — if the party is any indication, the Chengdu Worldcon will be a very familiar experience indeed.

Prelude

Almost immediately I’m "interested" in going, but I’m on the fence about attending for a very long time. At first the question is philosophical. Would attending the convention count as supporting the Chinese government? At some point, Peter mentions that he doesn’t think it does, and knowing that he has probably thought about it more than I have, I accept that answer. On the other hand, do I have a responsibility to go — to build connections with Chinese fandom, to counter the xenophobia I heard in the hallway conversations in DC?

Over time, the concern largely becomes practical. Would I be able to get a visa? I remembered having to apply for a visa in 2019 for the ill-fated 2020 trip, and needing an invitation from a resident in order to get one. How about lodgings? Looking briefly at Wikivoyage, it seems like there are regulations restricting the kinds of hotels a foreign tourist can stay in. Would it be safe? There’s stories from time to time in the news about the Chinese government not letting foreign tourists leave. Both the Chinese and the American governments engage in saber-rattling in the media from time to time; what would happen if open hostilities break out? (This risk becomes more acute after the Russian invasion of the Ukraine.)

Then there are more everyday concerns: what about food safety? Would I be at risk of a mugging? Might I get stopped by police at a checkpoint somewhere? (I honestly have no idea what to expect — on some level I’m mentally assuming an environment much like Cameroon.) Would I be able to get around? I took three semesters of Chinese in college, but I’m very rusty and I never would have considered myself conversational. I’m intimidated by the idea of traveling by myself someplace where I don’t know the language at all.

But the most important question is, would it be fun? I cast about from time to time to see if I can talk any of my friends into going. Ashley makes it clear right away that she is not going — "If you get into trouble," she tells me, "They’ll send the Marines. For me, they won’t send anyone." None of my other friends are interested either, but for varying reasons — one is expecting a child; one doesn’t want to go without his wife; some simply need more lead time than I give them. I have a sneaking suspicion that if I were, say, five to ten years younger, and possibly single, traveling to China would be a great experience, one that could completely change the trajectory of my life — but I already have a life trajectory by now, with a career and a committed relationship, and it feels irresponsibly risky to go. Not to mention that 2023 is already a busy year for travel for me, with trips to Cameroon and the Netherlands already on the docket.

For a while I am waiting for the Chengdu convention committee to publish visa information, figuring that until they do the decision is out of my hands. By the time they do, I no longer have time to get comfortable with the idea of going. I discuss it at length with many friends, but eventually I resign myself to the FOMO of staying home.

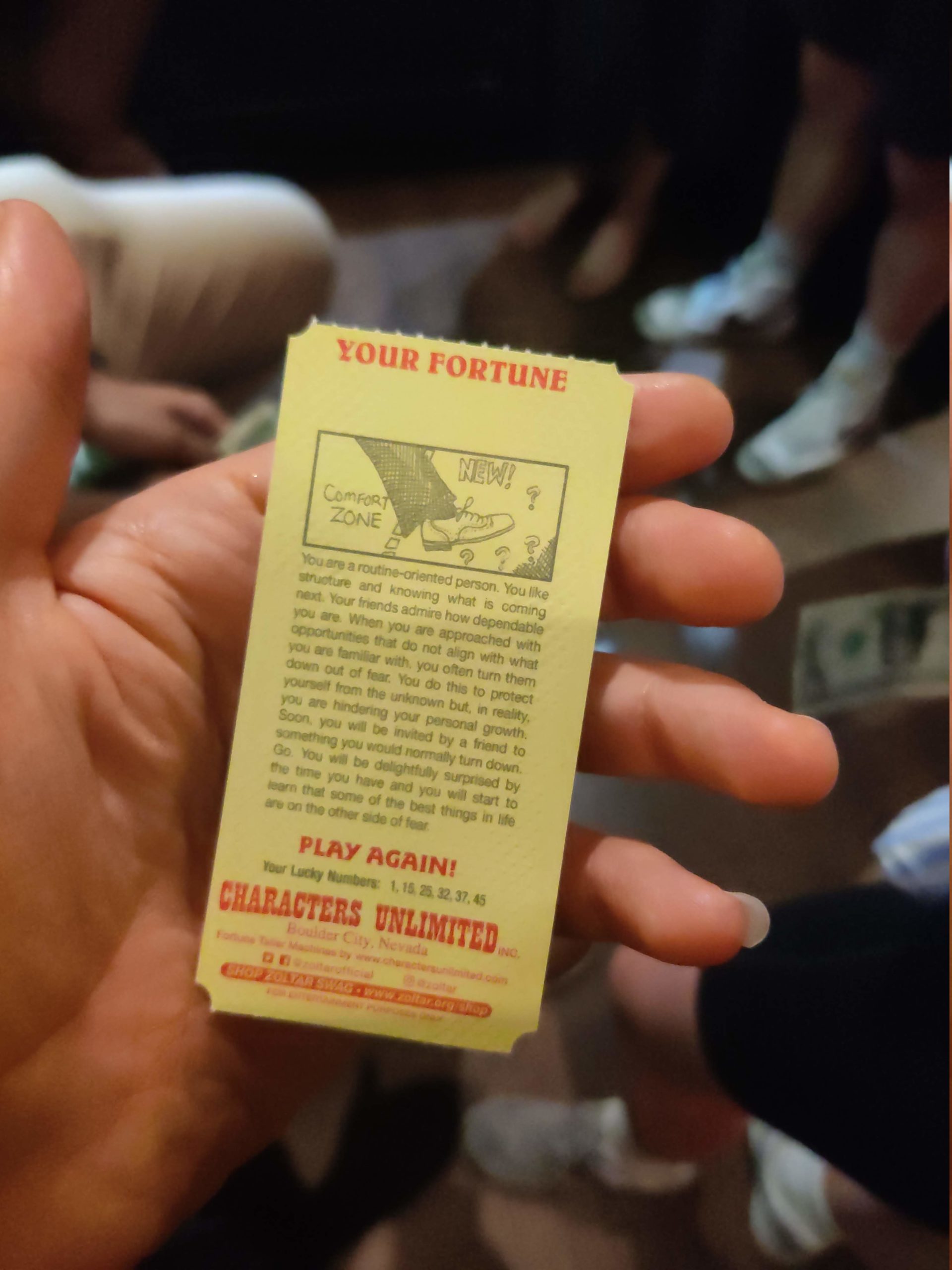

Then one day in August, I’m on a trip to San Diego for work. Some co-workers and I go to a magic-themed bar, and in the front of the bar is a machine entitled Zoltar. It’s an animatronic fortune-teller with a vaguely Near East theme. We all get fortunes drawn — for $1, the machine tosses off a humorous one-liner and prints out a slip of paper with a fortune on it. By now you probably know how much trust I put into randomness and fortunes…

… so when I read this, I knew immediately that I had to go to Chengdu.

Logistics

By the time I finally start planning my trip, it’s quite late in the game. One lucky break is that I realize that after that 2020 trip got cancelled, I never ended up using the visa I got in 2019. When I check my passport, I see that it’s valid for 10 years. Really? So the visa is taken care of.

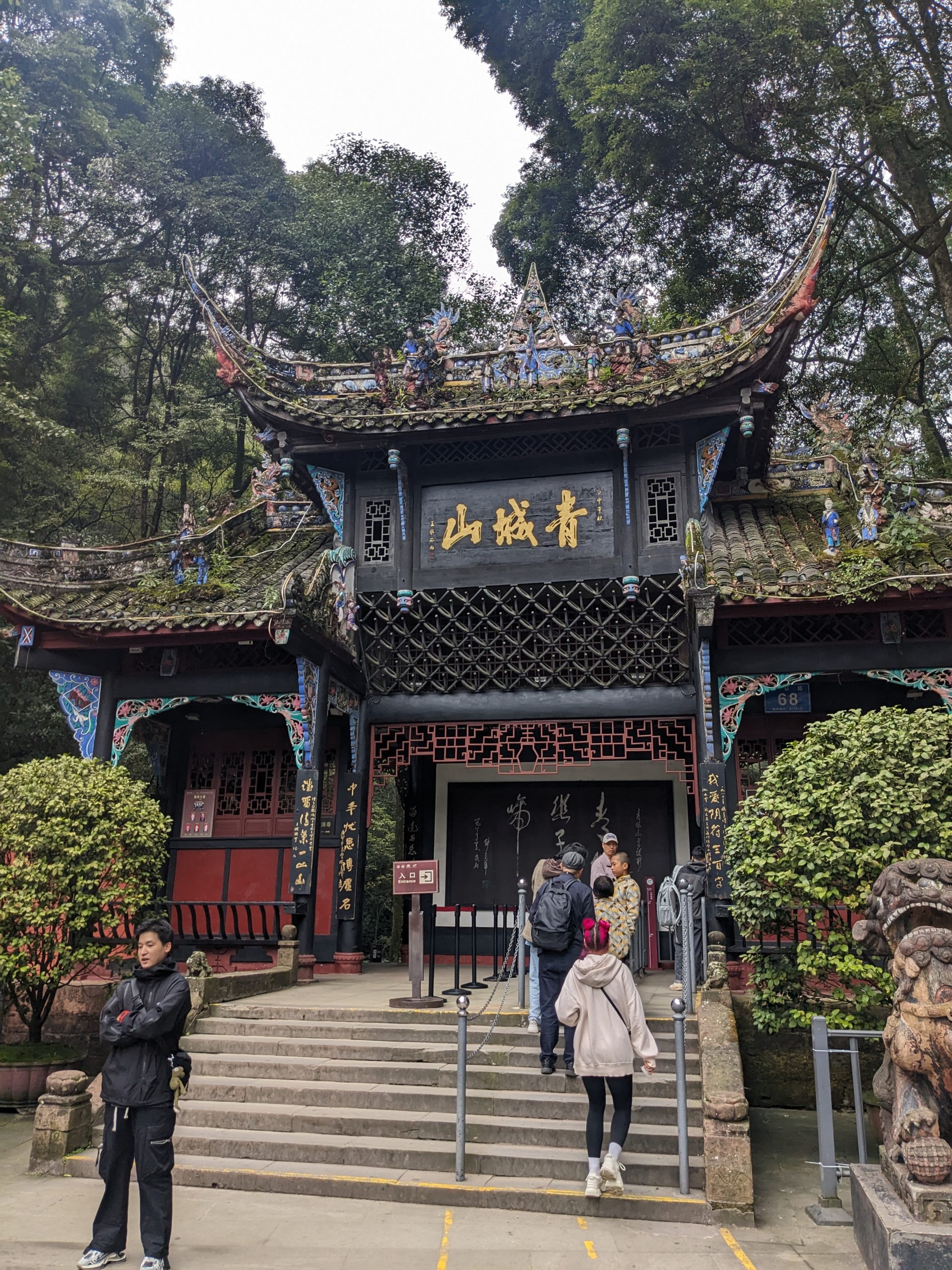

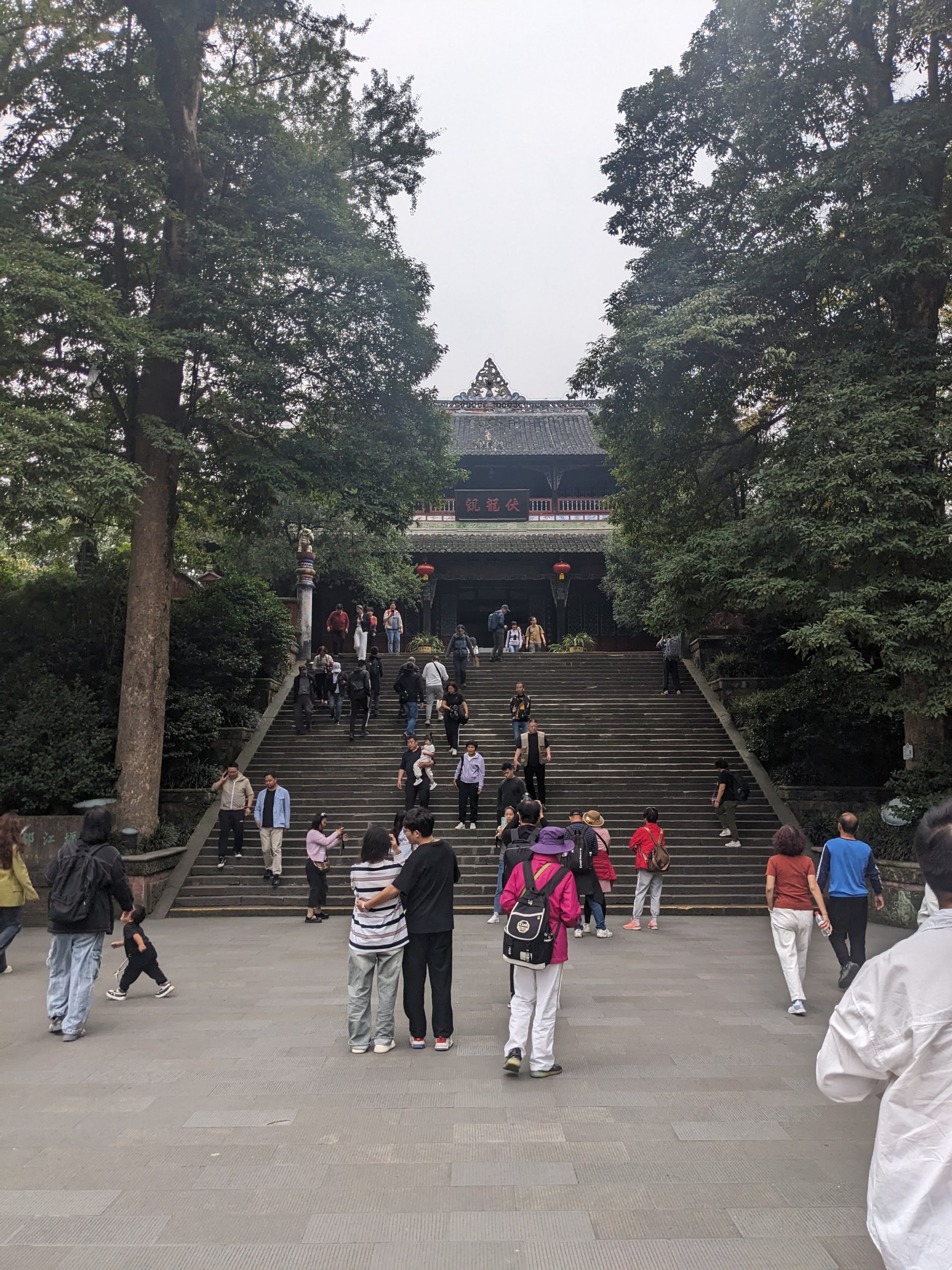

Flights are expensive, and I spend a long time trying to figure out my itinerary. I’m looking at 20-22 hours each way, and it doesn’t seem practical to just go for a weekend. At the same time, I want to attend the whole convention, which is five days, so I don’t really have a lot of time to see other places. China is a big place, and going to other cities you might have heard of — Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen — is not realistic, since they are all on the coast and Chengdu is on the western side of the country. Even so, there’s a lot to see. Even just Chengdu itself is huge — as many people as in the greater New York City metro area — and there are museums and old towns and historical sites. One surprising discovery is that when Peace Corps still existed in China, they had offices in Chengdu, at Sichuan University, and I wonder if there is still anything left, some plaque or monument worth visiting there. There’s even more stuff nearby. Lots of travel advice online encourages visiting places like Jiuzhaiguo and there are beautiful photos of places like Huanglong. But I know my taste tends away from nature and more towards cities, so between the airline schedules and the attractions I decide to fly into Chengdu, attend the convention, spend a couple days seeing the sights, and then spend a couple days in a nearby city called Chongqing before flying home.

Finding a hotel gives me the first taste of traveling in China. The convention committee has put out a list of hotels they’ve made arrangements with, but many of them don’t show up on Google Maps, and the venue isn’t there either. Of course Google products are not as well-developed in China because of the Great Firewall. For maps, the situation is even more exciting because of Mars coordinates [ed: link]. OpenStreetMap exists at about the same level of completeness as usual. Baidu Maps are probably the gold standard, but there’s no English support, and I don’t even try to manage it in Chinese. Even once I figure out which hotels might be convenient, the booking pages are all on a website called Ctrip, which doesn’t have any English either. The materials published by the convention include an email address to write to, to request help booking a hotel, and in desperation, I do.

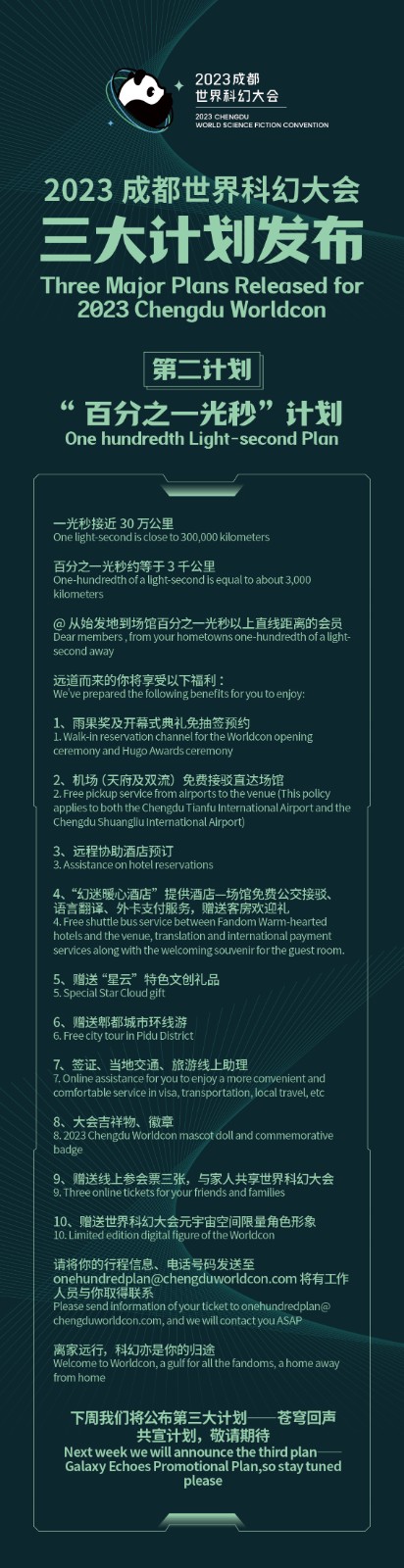

Around this time, I stumble across the three "promotion plans" that the convention has published — "The Stars and the Sea" Co-Creation Proposal, "Galaxy Echoes", and, most interesting to me, the "One-Hundrdedth Light-Second" plan.

It reads:

I pull up some city distances online. Three thousand kilometers essentially covers China, but pretty much anyone coming from a foreign country is going to qualify. And check out these words! "A gulf for all the fandoms, a home away from home". This feels very welcoming and sweet.

Another pleasant surprise comes up when I try to register for the convention. Apparently because I voted in 2021, I automatically have a free attending membership! I don’t know if this is because of the differences in currency value, or a campaign promise, or just another nice gesture to the community of international fandom, but I like it a lot.

I have some challenging exchanges over email with the convention staff (or are they volunteers? committee members?) to try to find a hotel. The closest hotel has already long since filled up, and so have several others, and it doesn’t really seem like I have a lot of choice, although it may also be that the convention has designated a hotel where they will have translators and that’s where they put me. I am torn between a desire to have an "authentic" Chinese travel experience and a desire to take advantage of the comforts that are being offered to me. In the end, I choose comfort and convenience and get a reservation at the Holiday Inn Express near-ish to the venue.

In terms of safety, it isn’t really clear how to best manage that. While I originally intended to plan everything in pencil — get refundable flights and cancellable everything just in case something should happen — I am too busy to actually buy travel insurance and in the end nothing is really refundable. The US Department of State has a travel advisory out about China, warning that the government "arbitrarily enforces local laws, including issuing exit bans on U.S. citizens and citizens of other countries, without fair and transparent process under the law". It’s hard to know how seriously to take this, since the warnings are even more dire than those for Cameroon (to which I traveled earlier this year). My friends who have been to China mostly advise me that I’m unlikely to be important enough for the Chinese government to care about, and so for that reason I should be fine. I read that the Chinese government takes drug use very seriously and even occasionally tests the hair of people for cannibis products. (I’m hopeful that if I don’t indulge for 60 days or so before going, that I won’t test positive.) While the guidance online is soaked in anxiety, it feels like if I keep my head down and don’t go looking for trouble, I should be fine. All the same, I find the STEP program and register there.

There’s one last concern, which is communication. There’s some discussion online, hard to know how seriously to take it, about Chinese border control officials asking to see your phone, perhaps to look for connections to politically sensitive organizations, and as a computer person, it feels like once a device leaves your sight, you can never really trust it again. So I order a "burner phone", a used Google Pixel, to bring with me, so as to not compromise the rest of my digital life. WhatsApp has a feature where you can "share" an account across multiple devices, so I can use WhatsApp on my temporary phone without removing it from my main one (at least, for up to two weeks). Of course, the Internet is censored in China, so I need to have a plan for how to access it, or at least enough of it to keep in touch with my family. There are lots of recommendations (including affiliate marketing) for different VPNs, but there’s a game of whack-a-mole between the authorities and the VPN providers and it’s hard to know which ones will work in China ahead of time, and of course you can’t download VPN software from within China. I get a one-month subscription to Mullvad for 5 EUR, download a few different apps "just in case". My backup plan is to get an eSIM with a provider like Holafly, which I think I will be able to load instantaneously if needed, and which will give me roaming data access, which is not censored. Finally, I create an email account with Hotmail, which is not censored in China the way Google products are.

Departure

By the time October rolls around I am thoroughly exhausted. My friend Boris visited from Cameroon in September, and although that trip went relatively smoothly, it’s always a handful. Then a couple days later I go to Portland for a work trip, and after I get back I only have one week before my flight. I’m scheduled to catch a late flight to Hong Kong and then a short hop to Chengdu. Departure is at 2 AM, and I find myself on the subway platform late on a Sunday looking down the barrel of 22 hours of travel time, with a visa I’m unsure of, to spend almost two weeks away from everyone and everything I hold dear. Why am I doing this again? I am so tired. I tell myself that if I have literally any problem at the airport at all, I will turn right around and go home. I will eat the loss but I will spend the time at home and I will get some rest and I will not complain. This soothes me enough to get to the airport. I have "Three Body Problem" by Liu Cixin on my iPad, which I start reading because I am confident people will be discussing it at the convention. It is a grim story but for where I am, alone on a train late at night, it is perfect.

The airport is remarkably smooth. I am early for my flight, which means I have enough time to brush my teeth while I wait. Eventually we all file into the plane. It’s Cathay Pacific, with a layover in Hong Kong. I find the HK fusion of British and Chinese fascinating, and I start to feel better almost as soon as I hear the accents on the public address announcements. This is going to be OK. We are going to have a fun trip.

They feed us dinner and breakfast. In between that and sleeping, I watch "From Beijing With Love" and "Weird: the Al Yankovic Story", as well as continue reading Three-Body Problem and start on "Infomocracy", by Malka Older. The flight is 16 hours, but the time zone difference is 12 hours, so although for me it is Monday evening, the clocks all say Tuesday morning.

We arrive at Hong Kong Airport quite early. It’s surrounded by hills reminiscent of the "gumdrop mountains" tourists to China are advised to see, and again I feel at ease, looking forward to the joy of exploring another country. Many of the concessions, especially the ones that serve alcohol, won’t even be open until my flight to Chengdu has already left. I wander aimlessly. The free airport wifi is the last Internet I will be on that isn’t censored, that I can still use WhatsApp and Google on. (An alternative plan might have been to buy a roaming SIM card in Hong Kong.) I walk essentially the entire length of the terminal.

Hong Kong Airport has a satellite terminal across an apron, which is accessible through this kind of airport overpass bridge thing. In the end I think my best chances for getting a drink (which I deserve! I’m on vacation!) is in a bar in that structure. It isn’t open when I pass the first time, but eventually I make it inside.

I have an Old Masters beer and a cocktail made with baijiu. The cocktail is interesting but the earthy flavors of baijiu are hard to work into a cocktail, and the fruitiness doesn’t quite work for me. Thus fortified, I head to my plane to Chengdu.

Cathay Pacific feeds us again.

Arrival

We get off the plane in Chengdu Tianfu International Airport. There appears to be some kind of tour group disembarking in front of me who are raucously conversing with one another. They are dressed like middle-aged men. In my sleep-deprived state, I wonder to myself if everyone in this country is a FOB. I go to the bathroom, but at the sink the bottle of soap turns out to be hand sanitizer. There are some attestations, which you can do online, except I can’t get on the wifi because it wants a phone number and my burner phone doesn’t have a SIM card. Instead I use a kiosk. I manage to fill out the arrival card and wait in line for passport control. I am on my best behavior. Then, another tour group wanders chaotically in. Their behavior is different. They are loud — they sound like they are yelling — and I don’t know what they are saying but they almost sound like they are arguing with the border control staff. Border control is not the place I would be doing that! They get on the foreigner line too, so I have no idea where they are from.

Border control takes what feels like forever. I’m watching the people in front of me struggle to do what seems like basic traveler stuff like getting their hotel information out. Eventually I get to the front of the line. The border control officer does not speak much English, and I don’t speak much Chinese, but they have a translator built into the desk, and this isn’t my first rodeo so I kind of know what kinds of questions I will be asked. In addition to the phrasebook and travel advice I have saved on my iPad, I also have a progress report from the convention, which has the Chinese name, so I show him that and he dutifully copies it down. They take my fingerprints. (For another American this may have felt totalitarian, but they did the same thing the last time I arrived in Cameroon.) Everything passes muster somehow and I’m through.

I think it’s a little old-fashioned to head out of the airport and have someone waiting for you with a sign, but sure enough, once I exit security with my suitcase, there is a young lady holding a sign for the Worldcon. This is one of the convention’s volunteers. I don’t know the exact arrangement but there are many of them and they are largely college-aged, friendly and helpful. She passes me to another volunteer, who takes me to where the shuttle will depart, offering to carry my suitcase (which I decline). There is some confusion once I get there because the hotel I will be going to is not one of the ones that the shuttle will go to. I will need to take a taxi from one of the hotels the shuttle does go to.

One logistical concern I have when I arrive in a foreign country is to get the local currency. A lot of people online say that China is a "cashless" society, and there is some of that — credit cards aren’t used much; instead lots of payments happen through mobile phone applications such as Alipay or Wechat — but of course I can’t use those because I don’t have cellular service yet. If I will be taking a taxi, I will need cash. I ask the volunteers if there is an ATM nearby. Two of them accompany me on a tour through the airport. The young woman speaks English quite well; the young man not so much, but he seems more confident about where we are going. The signs for the international terminal read "Int’l / HK, Macau, Taiwan Departures", which I find amusing. (Because of course HK, Macau, and Taiwan aren’t "actually" international from the perspective of the PRC.)

We take a shuttle train to another terminal, or perhaps it’s another part of the same terminal (we don’t take the shuttle train back). There are two cars in the train, and they open from opposite sides, perhaps to maintain a "before security"/"after security" division. There is no ATM at the other terminal either but we see a giant display advertising the convention. The convention’s marketing is very pervasive! Eventually we find a branch of ICBC or something and I manage to withdraw 2000 yuan (about $280). By the time we get back to the desk, the bus to the hotels has arrived. It is also heavily branded, as are four or five other buses we see in the parking lot. We load up; there are few enough people that nobody has to sit next to anyone if they don’t want to. I think I am the only person on the bus who is not fluent in Chinese.

We see more marketing materials almost immediately. Some include the "slogan" of the convention, "Meet the Future", which I like.

I tried to take pictures of the surroundings but it’s not easy from the bus. More dramatic hills, although most of Chengdu is relatively flat. Clearly development is happening everywhere. I’m starting to realize that on some level, I expected Cameroon, and this is a very different animal than Cameroon.

The bus ride takes a surprisingly long time — an hour and a half. The airport, I will later learn, is 75 kilometers from where we are staying — we circumnavigate Chengdu to get there. We are staying in Pidu district, to the northwest, near the end of the 6 line on the metro. The volunteers on the bus make announcements in Chinese and read their prepared equivalents in English. (They do a good job.) I get out at one of the hotels and look confused for a little while until someone comes up to me and asks in English if I need help. I tell her where I am going, and after a hurried conversation between her, the volunteers, and other hotel staff, she tells me that the best thing to do is to take a taxi to my hotel, and would I like her to flag me down one, which I absolutely would. How much will it cost? Probably around 10 yuan. I can only pay cash, and I only have 100-yuan bills, but she assures me that won’t be a problem. (This isn’t Cameroon.) She calls over a taxi and explains the situation in Chinese to him, explains to me in English that she has explained the situation in Chinese, and off we go. It’s only a few minutes, and sure enough, he makes change for me — he has to fish around under his chair for a Ziplock bag of cash, but he has change. I give him two yuan as a tip.

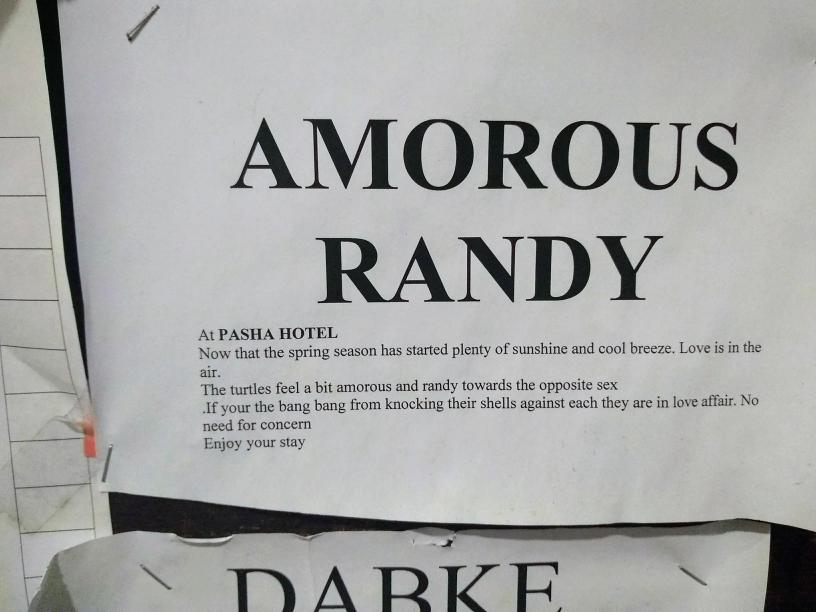

At the hotel, there are more volunteers waiting and able to help in case there are challenges with the hotel, but registration is smooth. I can pay with a credit card. I’m way too late to attend the "city tour" in the promotion, but the volunteers wish to give me a free gift, which I sign for. There is also a young woman in the lobby selling souvenirs. She is able to communicate in English to some extent, plus she is able to use her phone to access some kind of translation application when necessary.

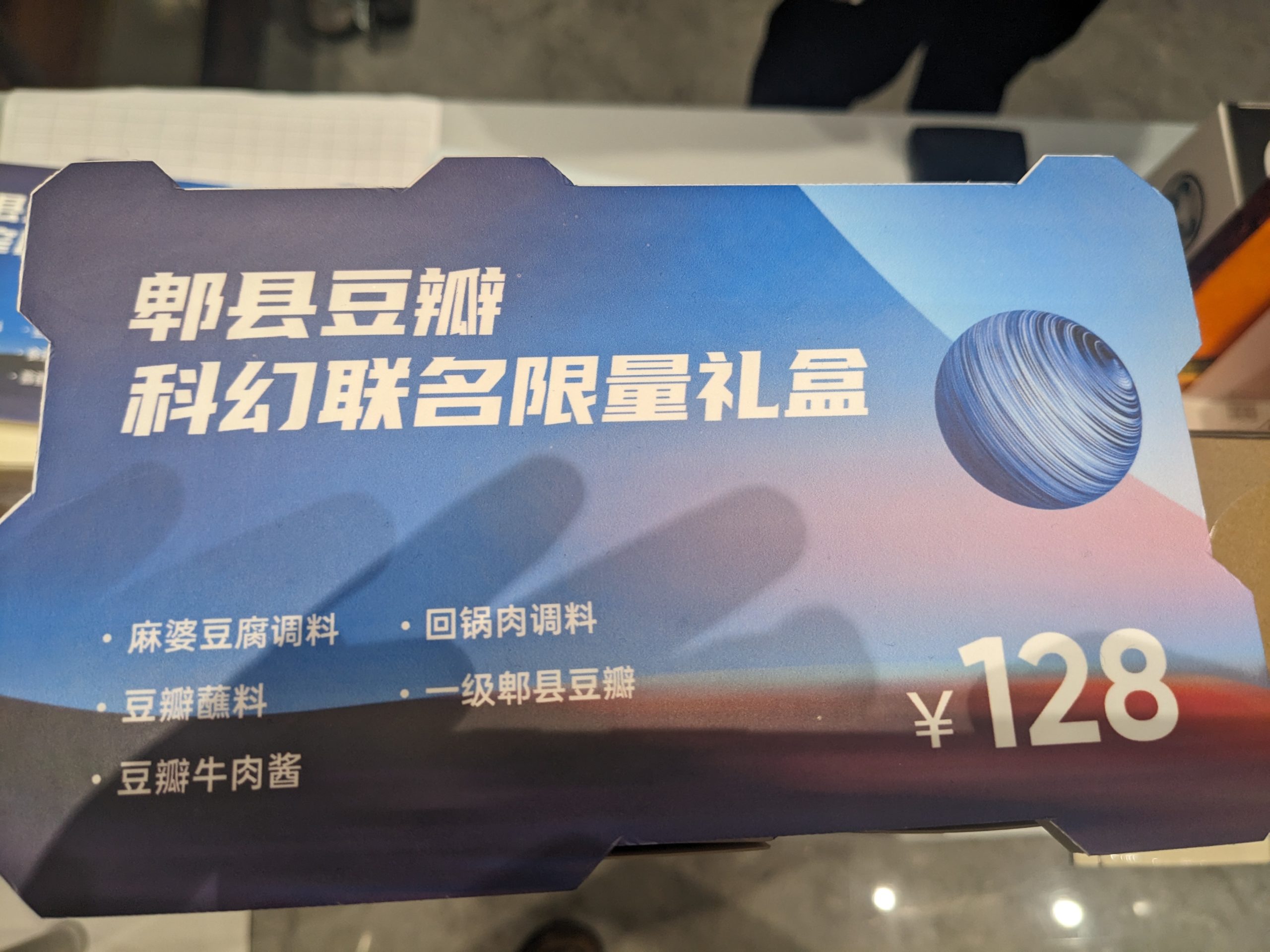

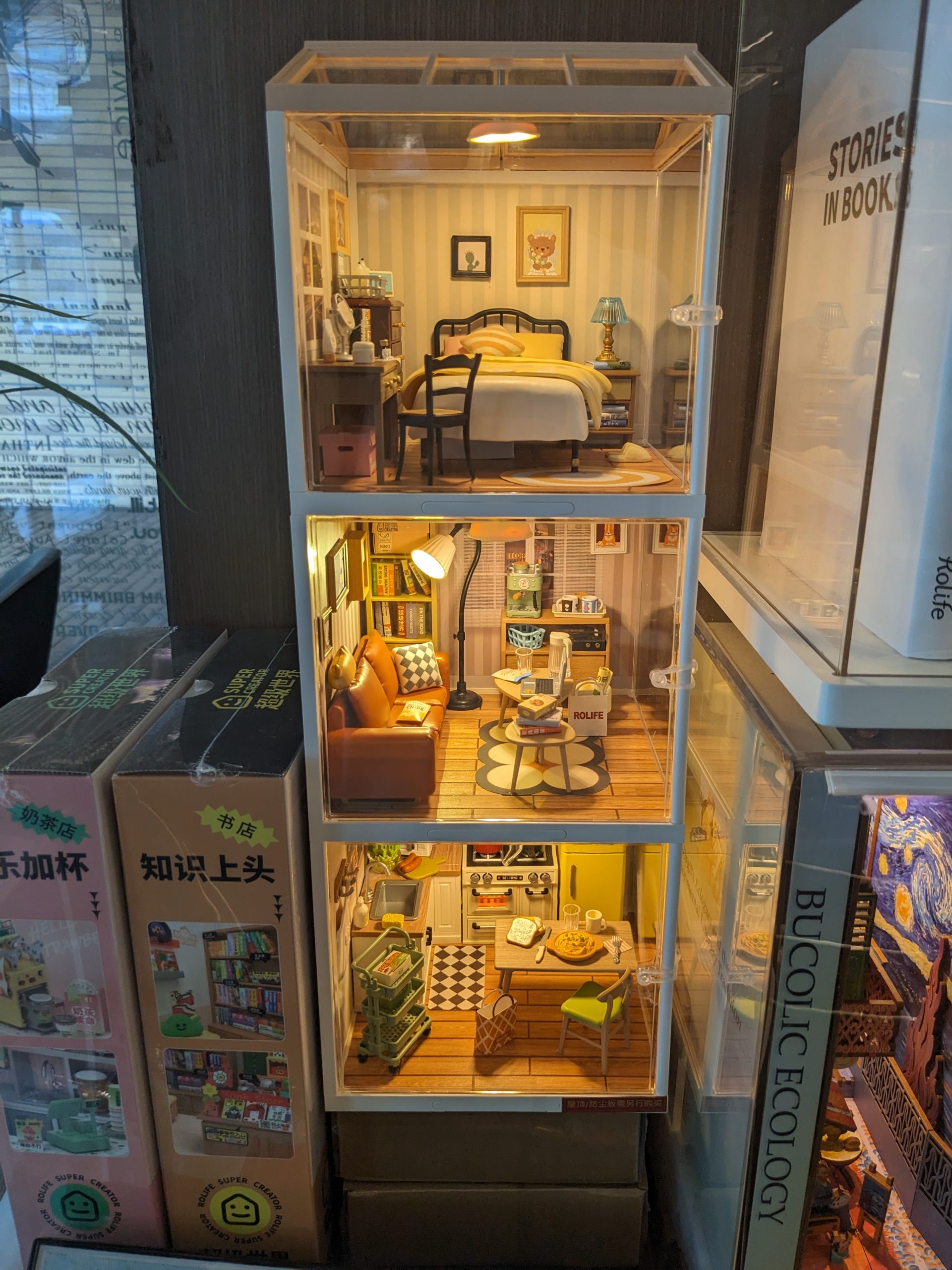

Prices are posted, which is very reassuring. This type of cup with a lid is apparently typical of the region.

Different kinds of tea.

I think these are different kinds of spices for Sichuanese cooking.

This is later in the trip but gives you a sense of it.

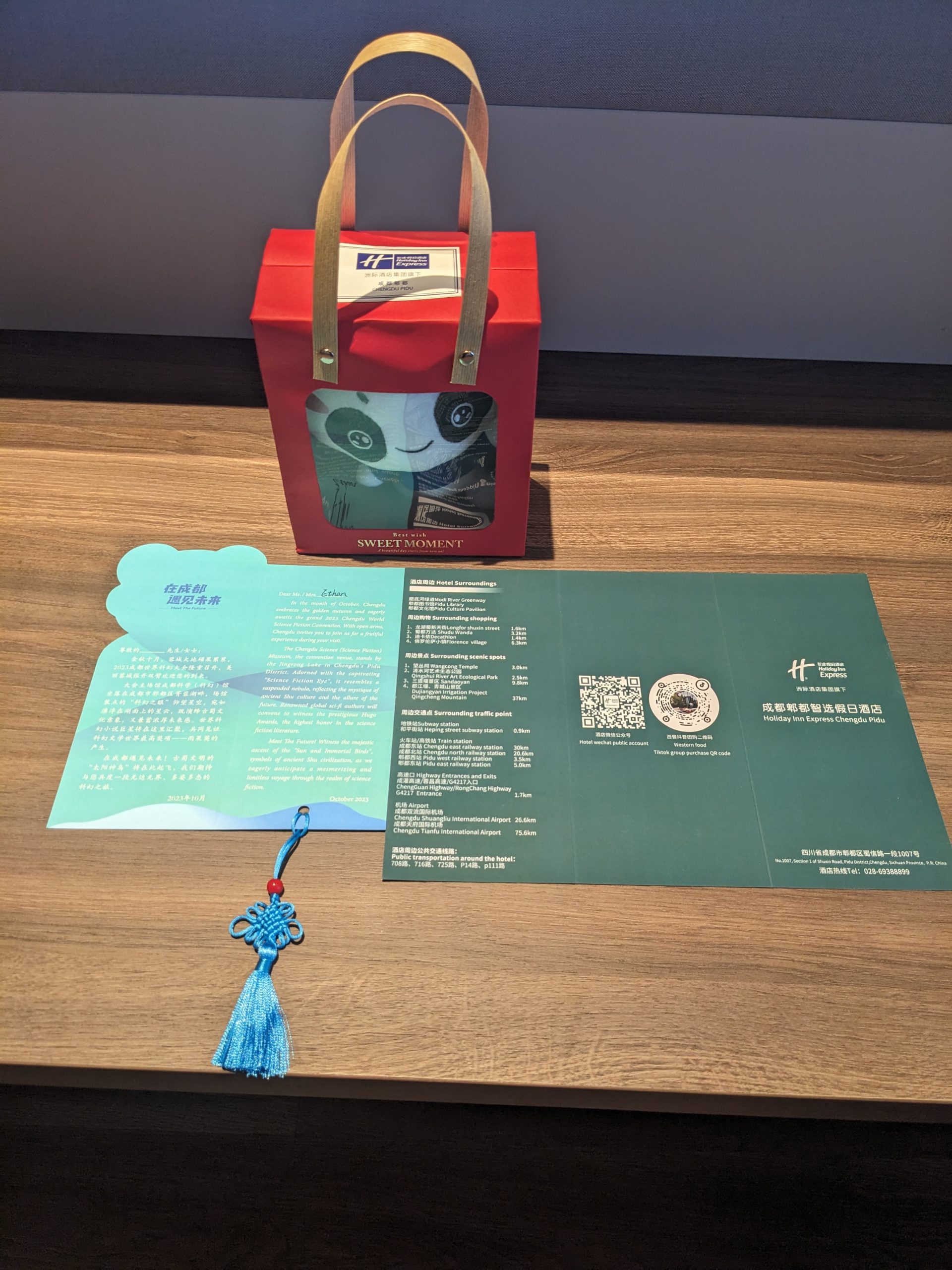

When I get to the room, I discover more free gifts.

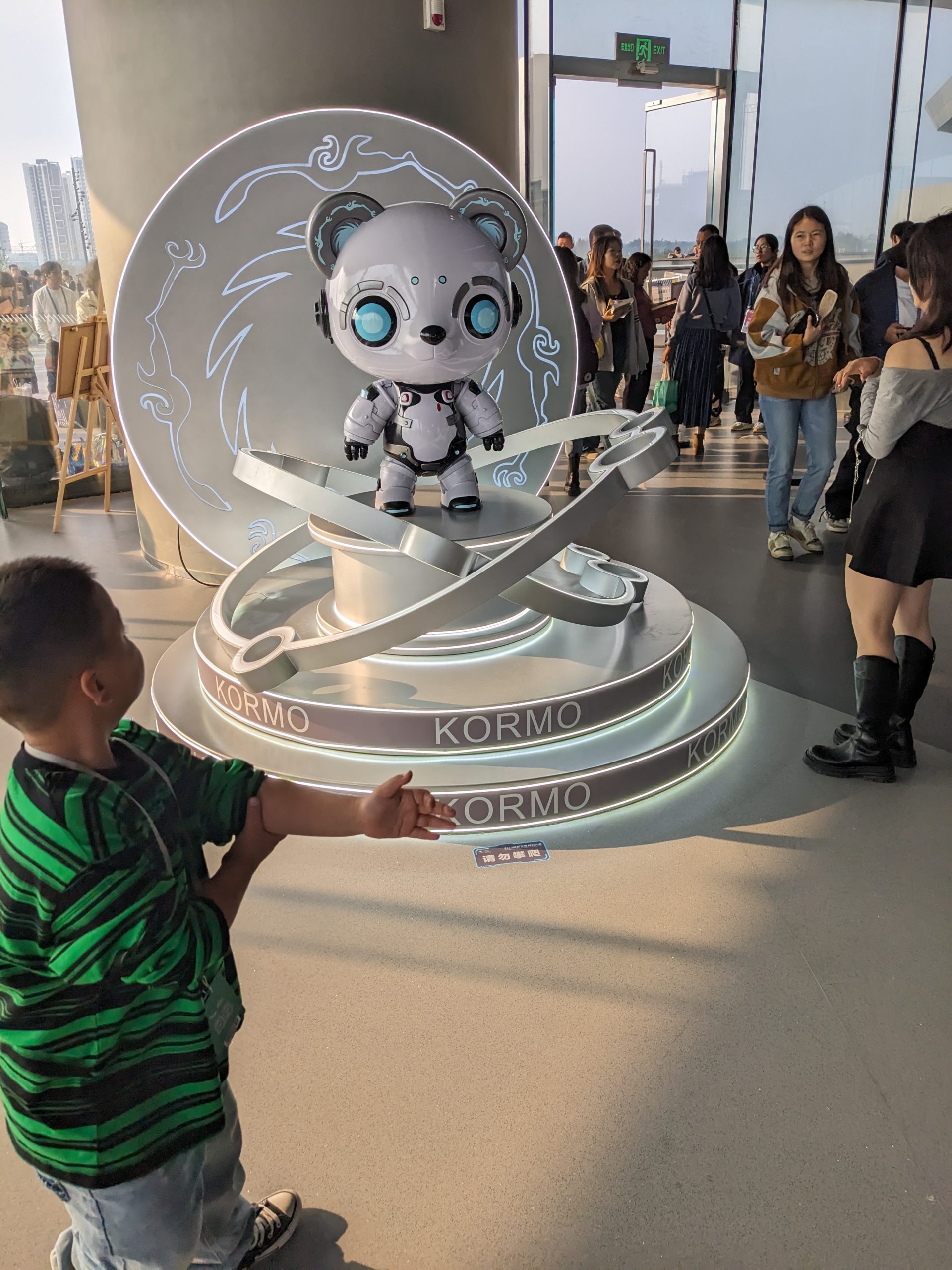

Here’s the free gift they gave me in the lobby. Inside are postcards, a model of the panda mascot (who I later learn is named Kormo), and a pin. Listen, Chinese Worldcon Bid, if you think you can purchase my affection with cheap trinkets, well, it’s absolutely working.

I try to settle in a little bit after a full day on the road. I’m able to verify that the VPN works fine. Although the sun hasn’t set, I’m still in the wrong timezone. I decide I need something light for dinner, and although the hotel restaurant seems convenient, it seems more interesting to explore the area. There is a haze in the air that is not fog but something more like smoke.

This cost me 16 yuan.

This is the Pidu Library, kitty-corner from the hotel. Of course there is another display here.

I stop at a couple supermarkets for dessert. The chew candies were like 1 yuan. The Oatly ice cream was like 13 yuan. To quote Wikivoyage, in China "basic items are relatively cheap, but the prices of luxury items are exorbitant". The shopkeeper also used his phone to help translate and I was able to ask what baijiu he recommended. (It was much like other baijiu I’ve had.)

This is the library from my room.

This is the view from my window. To the left is I think some kind of park.

Connection

The next morning I wake up before sunrise. I am able to finish my morning routine and go to the hotel restaurant for the breakfast buffet. I end up eating at the breakfast buffet every day that I stay there, and it’s actually pretty good. Among other things, they had great fruit juice, typically apple but on one day they had a kiwi juice which was great too. I’ll spare you most of the pictures but here’s a few from throughout the trip to give context.

In the background are Leadie and Sean, although I haven’t met them. This is the first day, and I eat by myself, but subsequent days I will mostly have breakfast with other convention attendees staying at the hotel.

This is the other side of the long table in the previous photo. Even further is a window where you can order certain foods — I ordered a dumpling soup and he pulled the dumplings out of a package in the freezer, which made me a little less enthusiastic about it. Even so, you can garnish with these. There are also some fried things in the bottom left of frame — these are quite sweet, I think the long ones were some kind of fried banana thing, and they were delicious.

Some steamed things available for consumption including potatoes and peanuts. The buns in the middle of the back row had some kind of vivid purple color that made me think they were not your standard red bean paste. I asked one hostess about it once and she gave me some name in Chinese but I couldn’t figure it out.

Some kind of small fruit.

At one point the hostess brings her phone over to translate for me that this dish is especially local, being from Pidu specifically. It’s a kind of radish dish. It’s pretty good!

I thought it was funny that Yi-Sheng was trying to take beautiful pictures of his food for Instagram, but then again, I guess I did the same sort of thing.

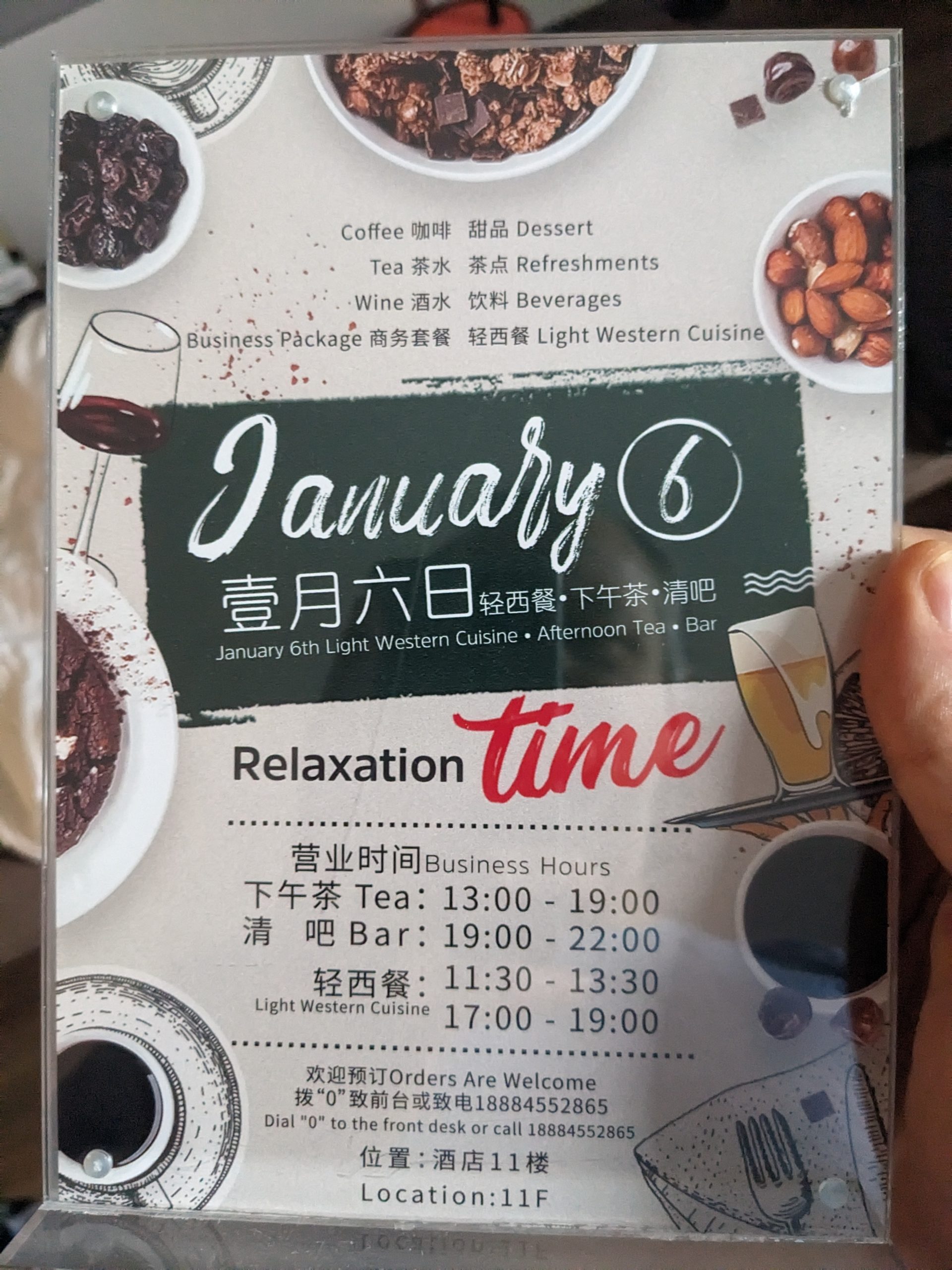

This is the name of the restaurant. I wondered if January 6th had any kind of special meaning here that it didn’t have for me, but couldn’t figure it out. In the end I used Google Translate to ask the hostess and she explained that January 6th is the date they "took the land", which I understood to mean that the hotelier received title to the property that they built the hotel on.

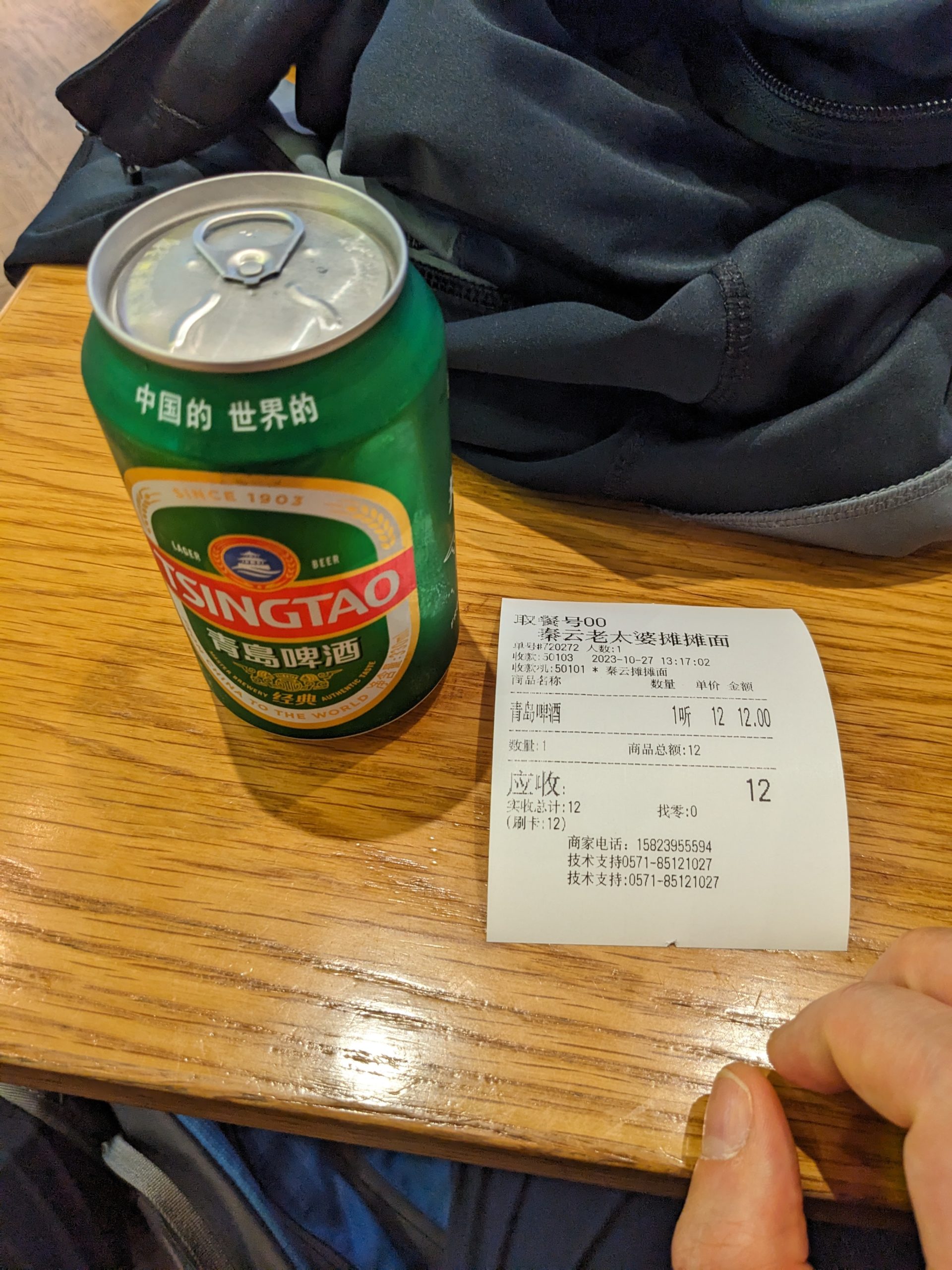

The hotel doesn’t have a separate bar; the restaurant serves alcohol, although it is only open restaurant hours. I never end up taking advantage of this service, although James apparently asks for a local beer and is offered Heineken or Corona. If you want to learn about the local libations, you will have to look elsewhere.

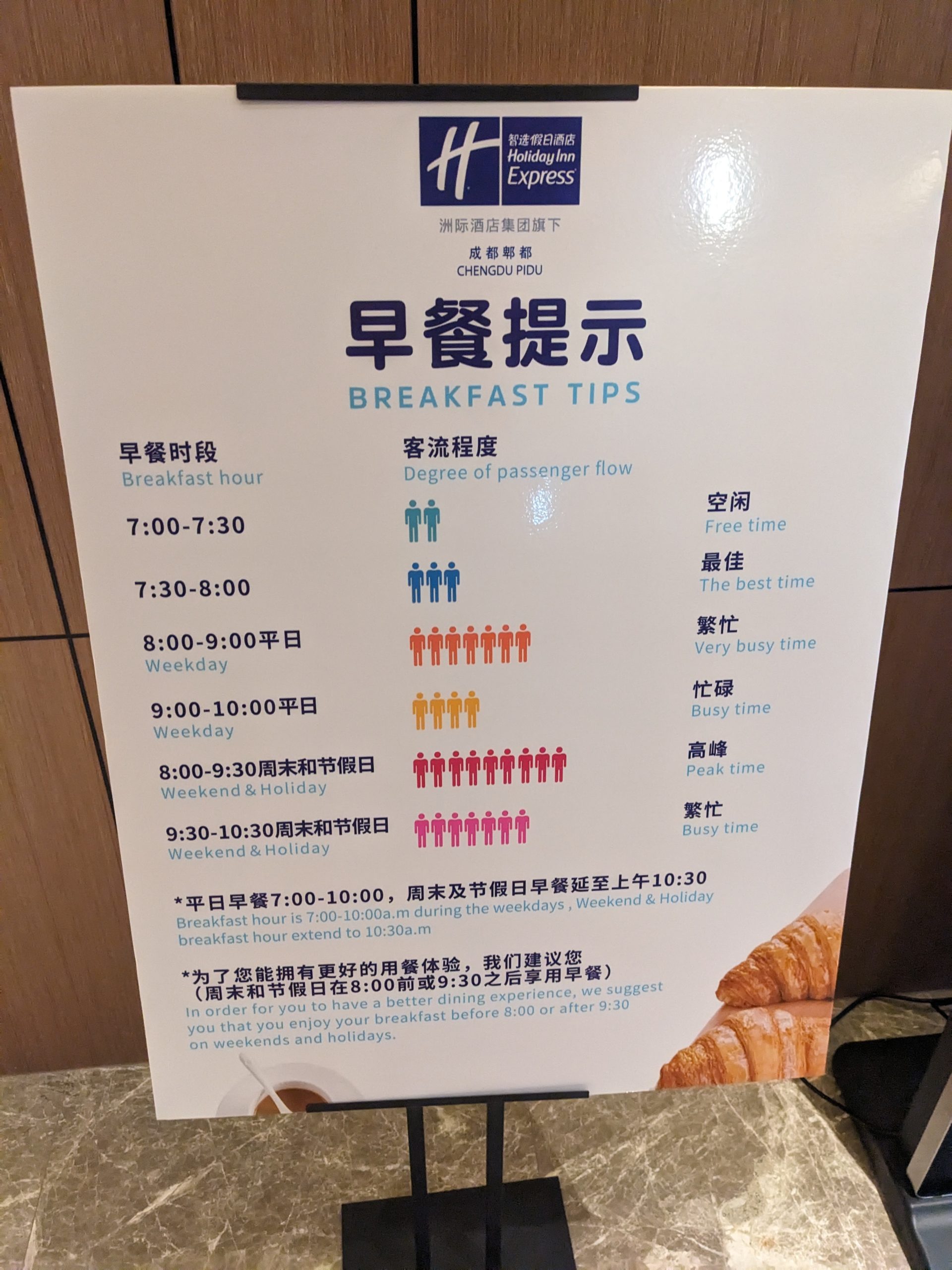

Advice on having an orderly breakfast.

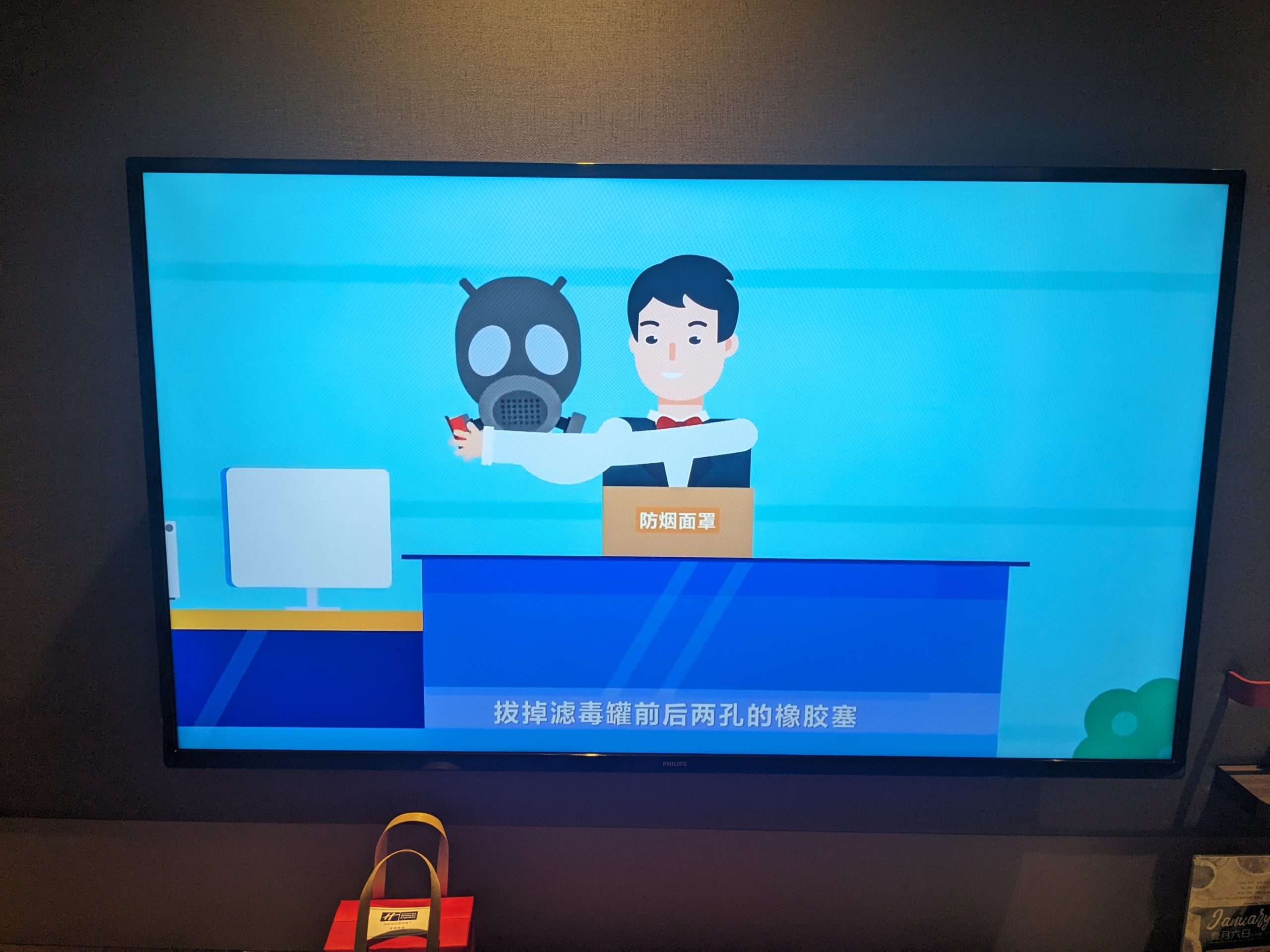

Overall the hotel is pretty nice. You can’t drink the tap water in China so housekeeping leaves you two bottles of water every day. One annoying thing about the room is that every time you come in the door, the TV comes on and shows you promotional videos and public service announcements. It’s not the end of the world but you can’t turn it off for like thirty seconds. As I’m brushing my teeth I see this spot out of the corner of my eye…

What the hell?? Is this some kind of nerve gas prevention thing? Is it about the smog?

Ohhh, no, it’s a fire safety thing. There’s masks in every room. Kind of a smart move actually!

The hotel had this little robot running around. He would say "excuse me" in Chinese. I guess he is dispatched to the rooms to deliver things to guests.

There’s a shuttle from the hotel to the venue and back every day. I end up waiting longer than I expect for the elevator to come, and then I decide on to get off to look at the hotel "fitness center". I’m sure that there will be a couple minutes of leeway for the shuttle, right? The shuttle is at the curb when I get there but at exactly the departure time of 8:30 AM, the door is closed and I can’t figure out if I’m allowed to get on. For once, looking confused isn’t causing anyone to rush to my aid. The shuttle leaves without me.

The volunteers, when I get their attention back in the lobby, regret to inform me that the next shuttle isn’t for several hours. That’s fine, I say — there’s another piece of business I want to get taken care of, namely getting a SIM card. Is there a place I can do this? The advice on Wikivoyage is that most branches of the telecom companies are only able to register Chinese nationals — if you have a foreign passport, you might have to go to a central office downtown. The volunteers call around and find a nearby China Telecom branch which will be able to help me. "How much money do you think I will need?" I ask, since I have only taken several hundred yuan, preferring to leave the rest in my room in case I get mugged. "That should be plenty," they assure me. They offer to call me a cab, but when we get to the street, no cabs are forthcoming. How far away is it? Maybe a 20 minute walk, they guess. OK, in that case I’m happy to walk it. (They seem surprised at that, but I assure them that New Yorkers walk quite a lot.)

I set off — it’s further than I expect but walking is fine and I get to see a little bit of the area. As I cross the final street to get to the office, I notice what look like train rails in the street. It turns out there is a tram line! I am eager to ride it later but want to get the lay of the land a bit more first.

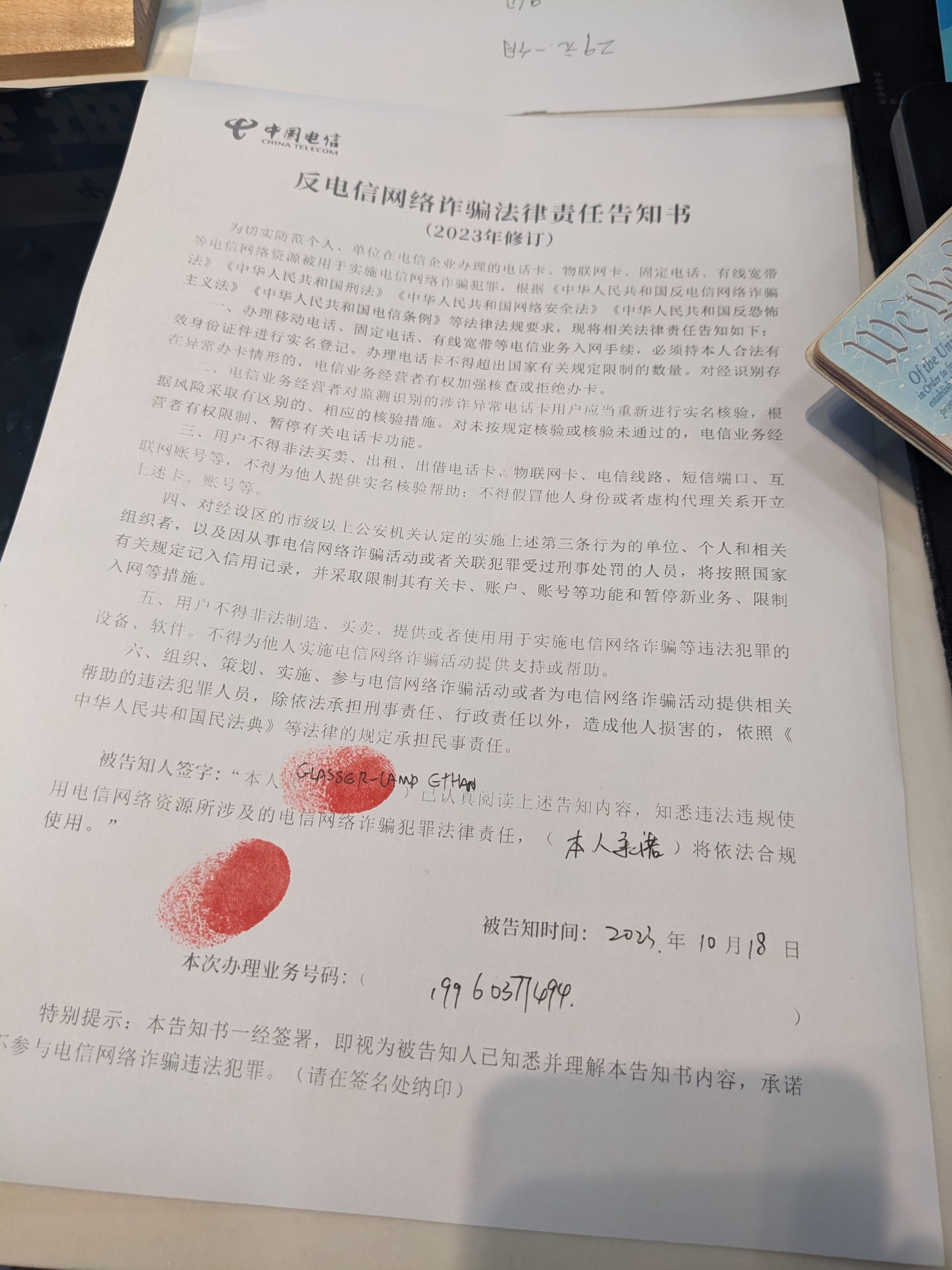

The staff at the store are solicitous — first I try to explain my situation in my halting Chinese to the front desk, and they give me a number like at the DMV. I am seated in front of another young lady, along with a young man who floats in and out of the conversation. They use their phones to translate and we are able to conduct business. They start by saying they will try their SIM card in my phone to see if it works. It doesn’t. The gentleman tells me through the translator app that it’s because of the frequency bands used in China — my phone doesn’t support them. (This doesn’t sound right to me because I had deliberately selected the Google Pixel based on the LTE bands it supports, which should include the ones used in China.) Still, I can buy a phone from them as well. They have a used phone they can sell me for 400 yuan, plus the SIM card with 200 yuan of credit. Unfortunately I can’t pay digitally. I tell them that I only have 500 yuan (a negotiating tactic I learned in Cameroon, which also happens to be true) and they agree to lower the price of the phone to 300 yuan. Once it’s all settled, we go through the processes of signing up for their network. This mostly involves me "signing" lots of agreements by writing my name in print exactly as it appears on my passport. They also get me on camera and have me recite some kind of vow in Chinese, which I have no idea what it was but I assume it’s something like "I understand that using this device to perform crimes is bad and I won’t do it".

They also make me stamp this document with my thumb. (They have a little packet of tissues to use to wipe your hand afterwards.)

They give me the phone with the SIM card inside. It seems to work fine, but it’s entirely in Chinese and none of my data or applications are on it. It’s not running Lineage but some kind of weird Android fork. I’m not excited about the situation but it’s still an improvement. Maybe I can use it as a hotspot and VPN in from my other phone or something, or maybe I can figure out what’s wrong with the phone or the SIM card later. Before I leave, I ask for one of the devices they use to press the release to get the SIM card out of the phone. The woman smiles and gives me two paperclips.

From here I walk to the convention — about which more later. However, I’m still dissatisfied about the phone situation. When I get back to the hotel that night, I try to figure out what happened and why my phone didn’t work with the China Telecom SIM. When I put it into my phone the settings just say "Out of service". Using the hotel wifi I search around a lot, trying to figure out what LTE frequencies it might be using and how to find the ones my phone uses, or why this specific error message. In the end I find this discussion on an Estonian Sony users forum which links to a site called FrequencyCheck which reports that "This carrier only accepts approved devices on its network." Son of a gun! So it wasn’t the frequencies! The next day I decide to find one of the other major mobile operators in China and see if it works any better. I try to find some on the map but in the end I happen to see a storefront for China Mobile on the way and stop in. I have a tab open with Google Translate and an explanation of my situation. The staff there are also helpful, and when they put the SIM card in to the phone it works right away. They seem confused about it, as though they were expecting to have to console me about the phone not working and have to be convinced that they don’t have to. Still and all, we conduct business again through the translation apps. The first woman I speak to seems somewhat befuddled, and the colleague that takes over for her speaks loudly and assertively. (Perhaps this is the origin of the reputation Sichuanese people have as fiery people.) The staff seem to want to sell me something involving a subscription plan, which makes no sense, and then we have a failure to communicate because I want to know whether I am required to come back to the store when I leave the country to cancel my subscription, and they are trying to tell me about a prepaid SIM where I will have to forego the balance on the SIM card if I don’t come back to the store to exchange it. In the end I am able to get the SIM card for quite a bit less, I think under 100 yuan but I don’t remember exactly. The business proceedings are much the same except instead of having to repeat a long Chinese sentence into a camera, I only have to listen to a computerized statement and then say "Tongyi" (meaning "agree") at the end.

I decide to take the used phone, which I no longer need, back to China Telecom. To their credit, they are happy to refund the phone and exchange the SIM card for the credit remaining (a little less than the 200 yuan I started with). I try to explain to the clerk (the same one as yesterday) that in the end the problem wasn’t the frequency, that China Telecom blocks devices, that I am able to use the phone correctly on the other company’s network. She doesn’t seem to understand but she proceeds with the transaction (with a little less ceremony than the day before). Later, she asks (perhaps as part of the close-account process) "Why did you decide to use China Mobile instead of China Telecom? Do you like them better?" I’m not sure how to get through to her but I translate back through the app that China Mobile worked for my phone and China Telecom didn’t. She smiles and writes back "It’s OK. Everyone can have a preference", perhaps assuming I feel shy or awkward instead of being frustrated about the inability to communicate. "Please tell your co-worker," I say again through her telephone. "It’s not the frequency." That’s the best I can do — except, perhaps, write about it in this blog.

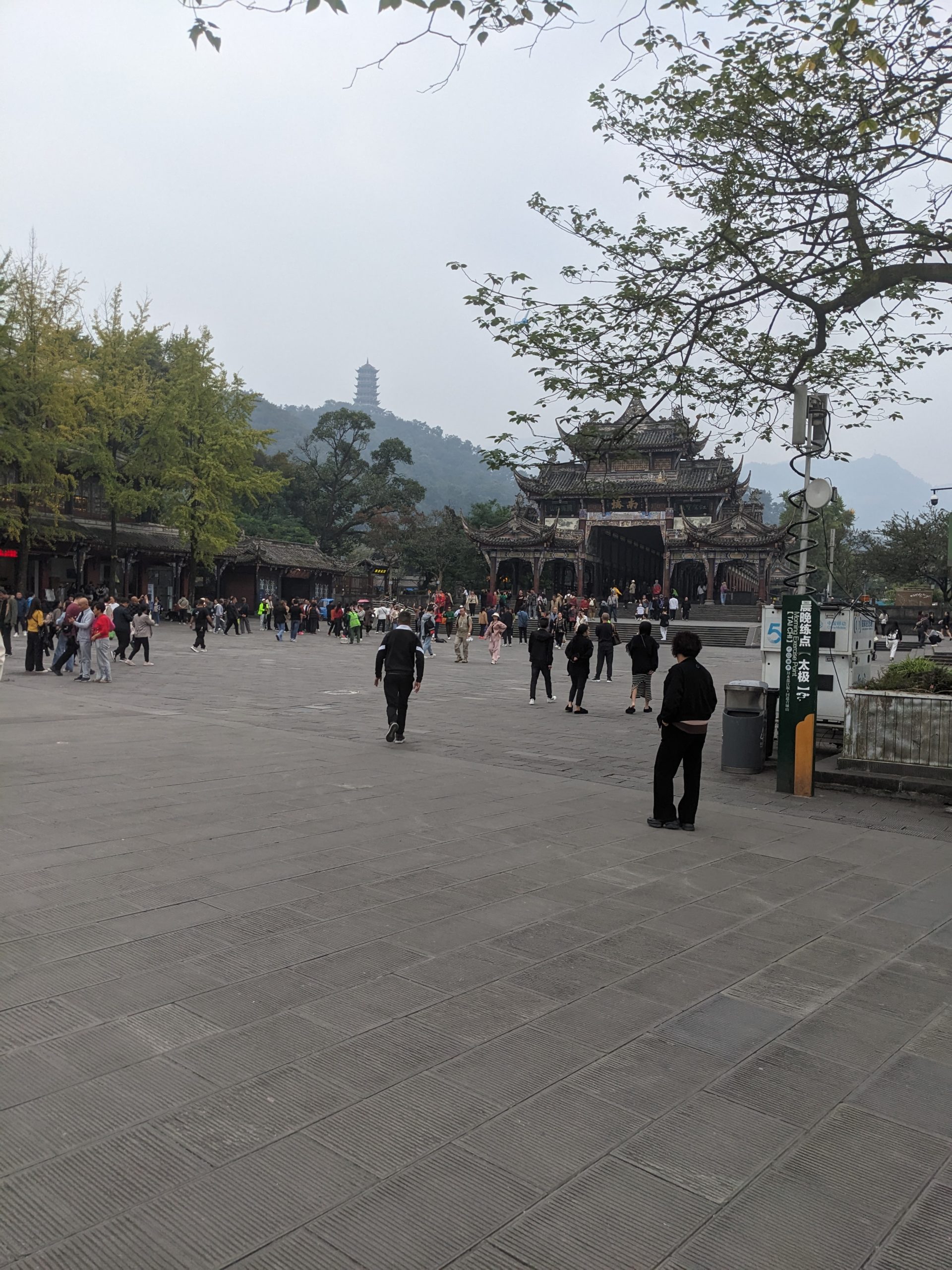

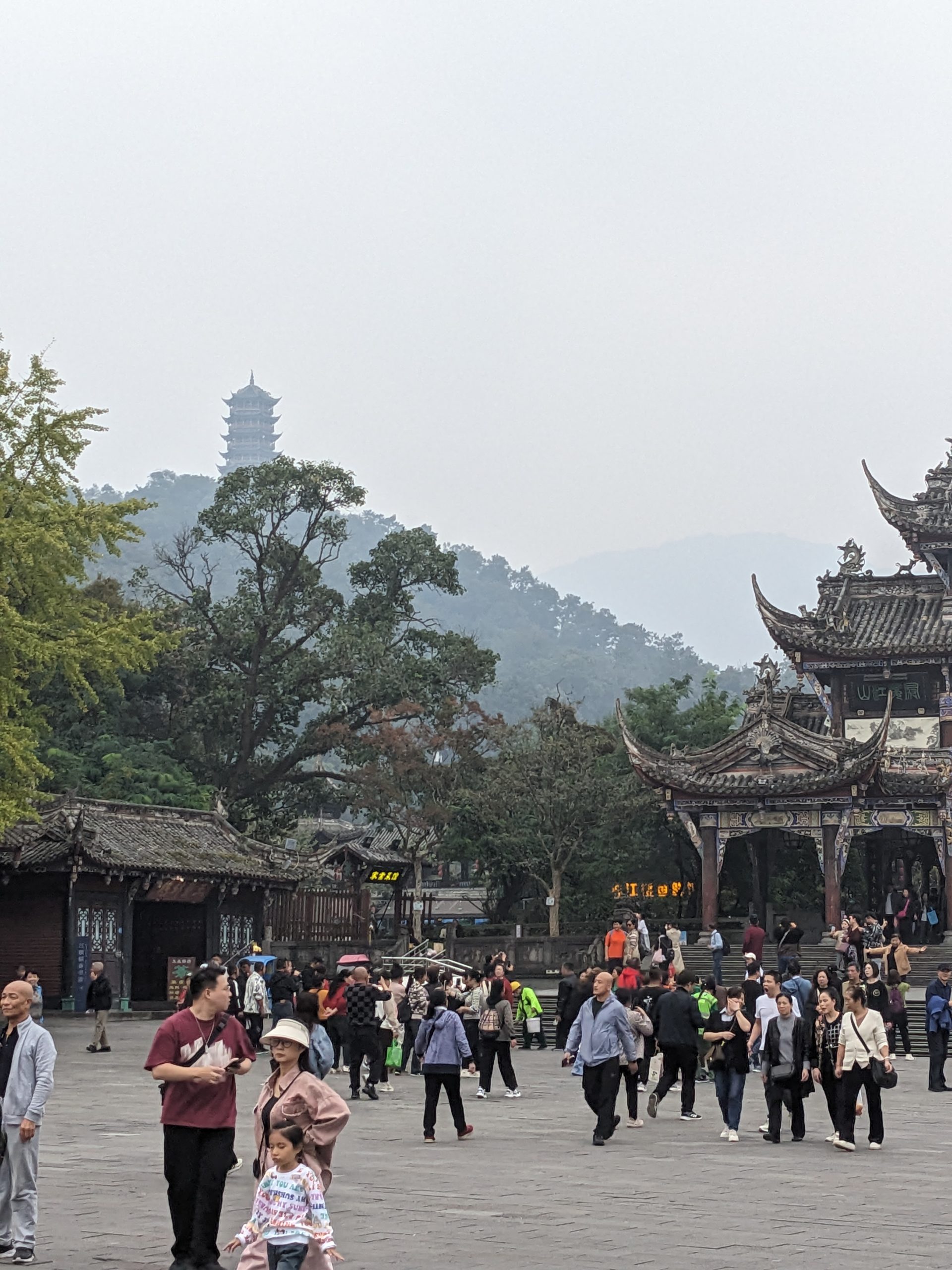

Let’s skip back to leaving China Telecom the first time. I decide to walk to the venue rather than trying to go back to the hotel and getting more help from the volunteers. I’m pretty sure I know where I’m going based on the map and I want to see more of the city if I can. I stop on the way and successfully a plain steam bun in Chinese.

Some bike parking I pass on the way. Chengdu seems to have a lot of bike infrastructure, which doubles as moped and scooter infrastructure, and to be relatively flat. You definitely see bikes here and there, especially in the populated areas. There’s also a bike share program. The urban environment feels modern somehow, with the frontage of every street full of businesses and with huge residential towers often looming behind them, along with a certain amount of parkland and gardens to break things up.

I also ask a security officer about the tram, and although I don’t understand almost any of what he says, I do learn that you don’t buy tickets; if you can’t pay with your phone, you can pay when you board and it’s only 2 kuai to ride.

On day 2, after I return the used phone, I definitely ride the tram.

Convention

Oh lord, I’ve already been writing for almost 8000 words and I haven’t even gotten to the convention yet! Oof. Eventually I cross the road whose name is in the instructions about where to pick up my badge. They’ve blocked off several roads and I am able to follow signs. Once again, volunteers leap into action when they see me and helpfully guide me to the registration desk — past a maze of temporary crowd control fences, almost entirely empty, through a special channel for international visitors to a pair of dedicated desks manned by English-speaking volunteers. I give them my passport — the volunteers at the hotel insisted on informing me that I would need it, though of course I always carry it on my person when in another country — this might be a cultural thing; I think in China the passport is more like a birth certificate, a precious document that you would not normally walk around with. Before long I have my badge and I am directed to another desk to get another "free gift", which turns out to be a program book, which I don’t look at for the rest of the convention.

The entrance gate is still quite a ways from the venue, and once you get to the venue, there’s a security bag check. In my bag is the bottle of baijiu but nobody says anything about it. Instead they find my water bottle, which they ask me to drink from, to prove its safety.

Apparently trees can have IVs too.

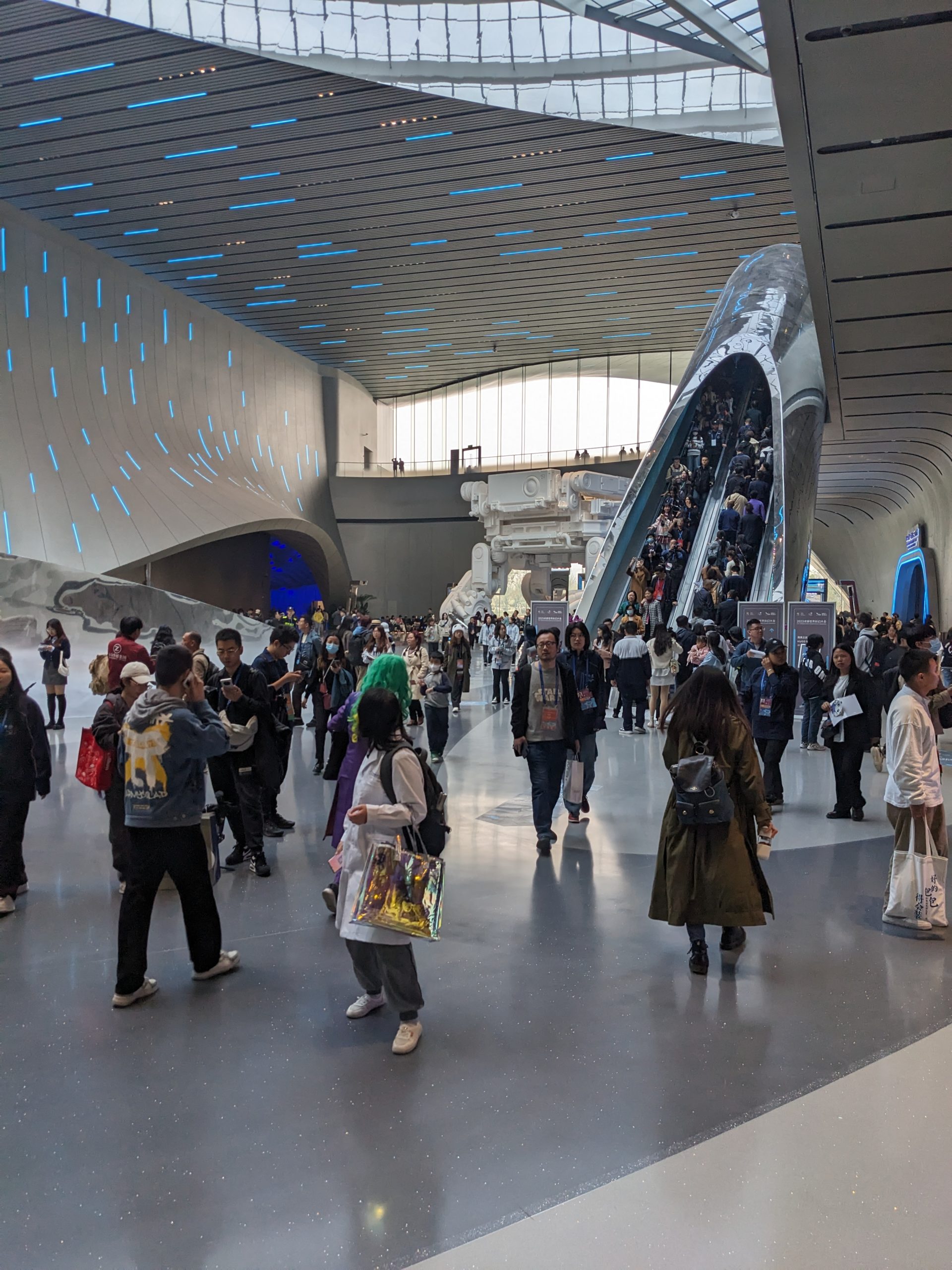

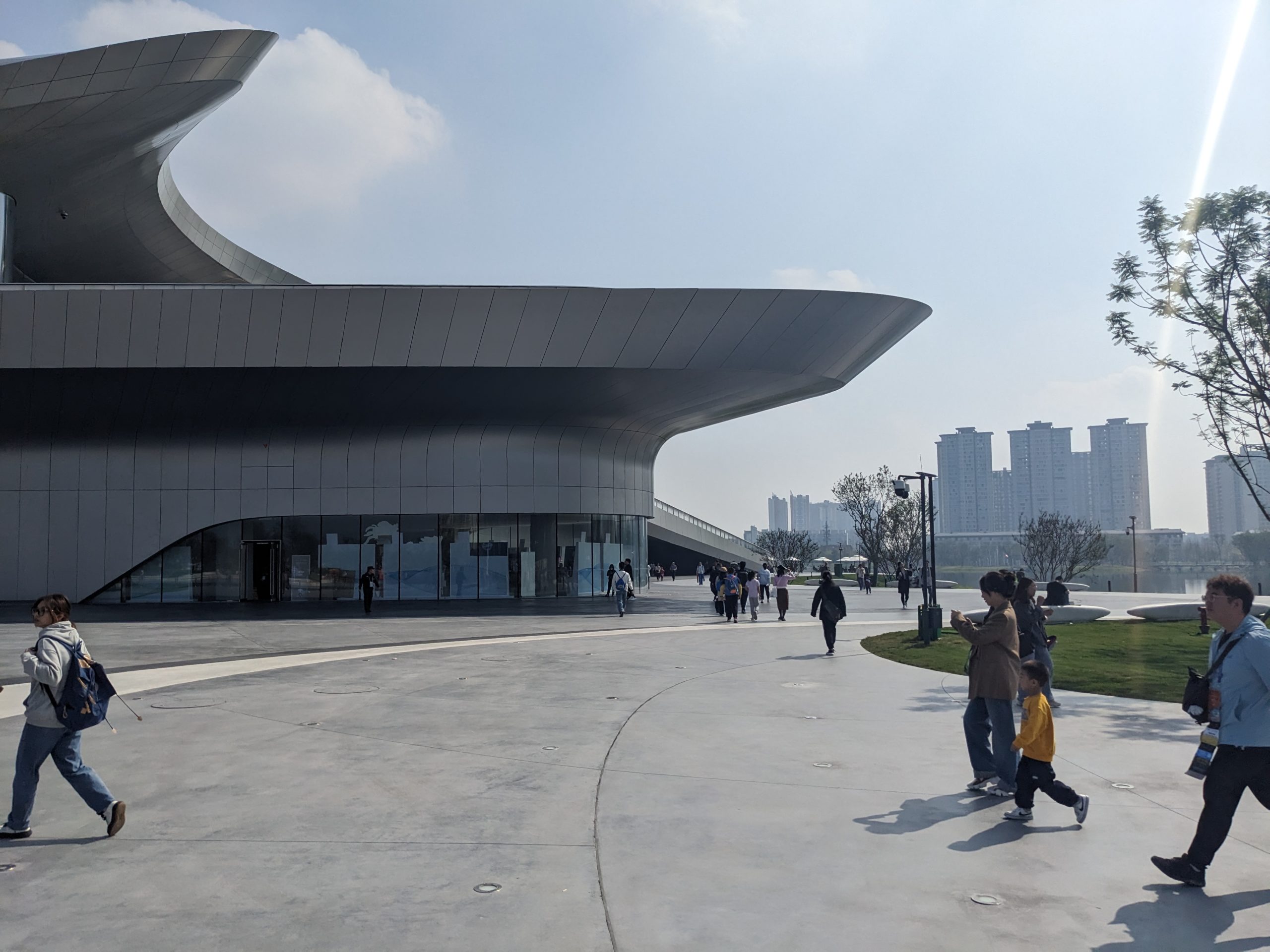

I spend a while just wandering around and seeing what the whole place is about. Wednesday, being the first day, is a little empty and a part of me wonders or worries whether the event had been overpromoted. Although the venue is described as a "Museum of Science Fiction", there isn’t really much in the way of what you might call "exhibits". It felt like construction had just barely managed to get the building done on time.

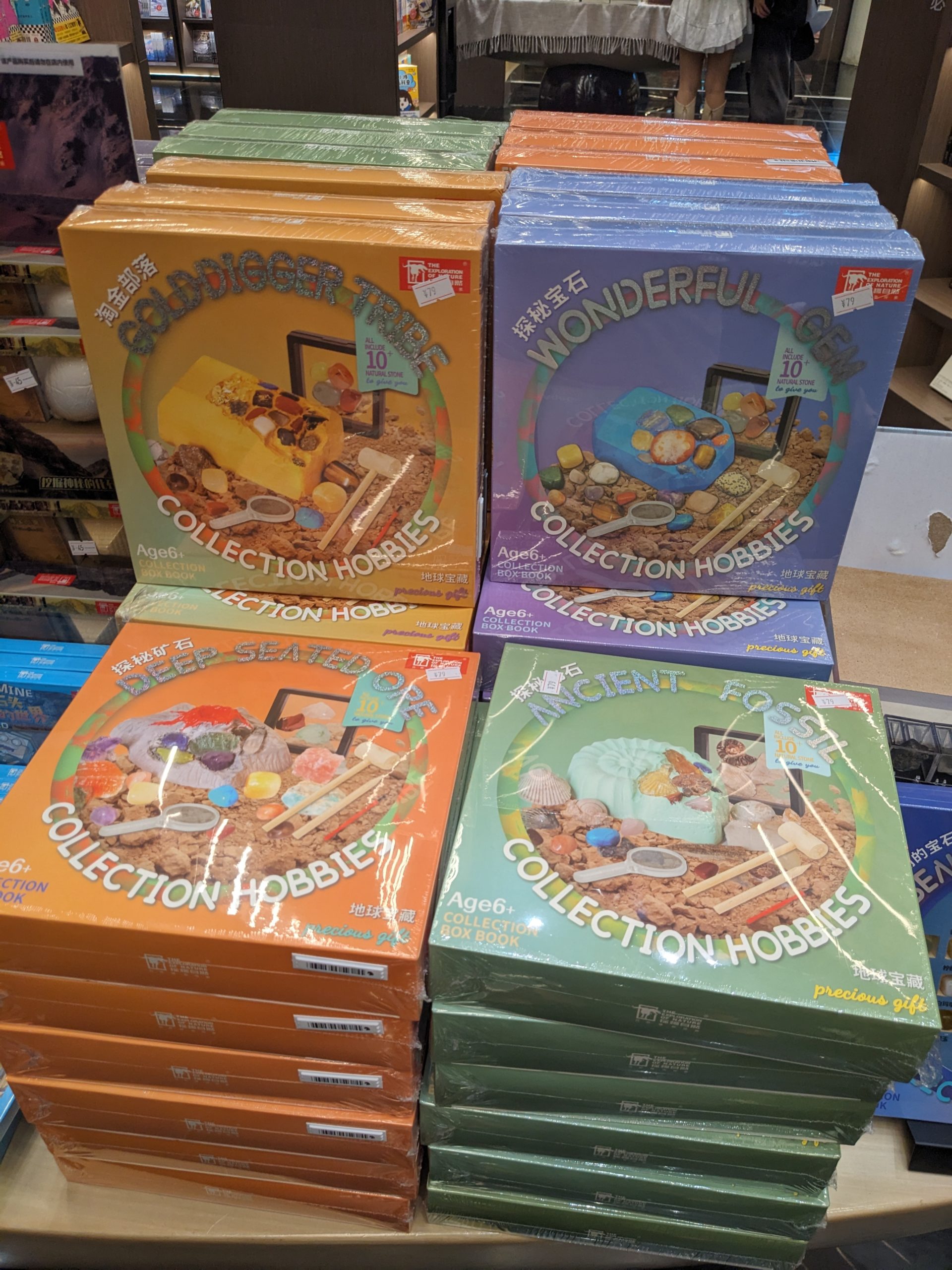

I love the translation "Derivative Products Store". This appears to be some kind of official merchandise store, selling products related to many franchises. While I am here, more friendly volunteers come up to me and talk in English. Everyone seems very friendly!

One group has this big roll of paper which is open to anyone who wants to draw something. I draw the outline of New York State and write "Hello from New York".

I think it’s the same group that has these cool light-up signs. They also give me a gift of postcards.

One of the vendors. Look for fellow travelers. This is in the vendor area. Seattle 2025 has a table there and I have a pleasant conversation with the gentleman on the other side of it. He is the first non-Chinese I have met so far today.

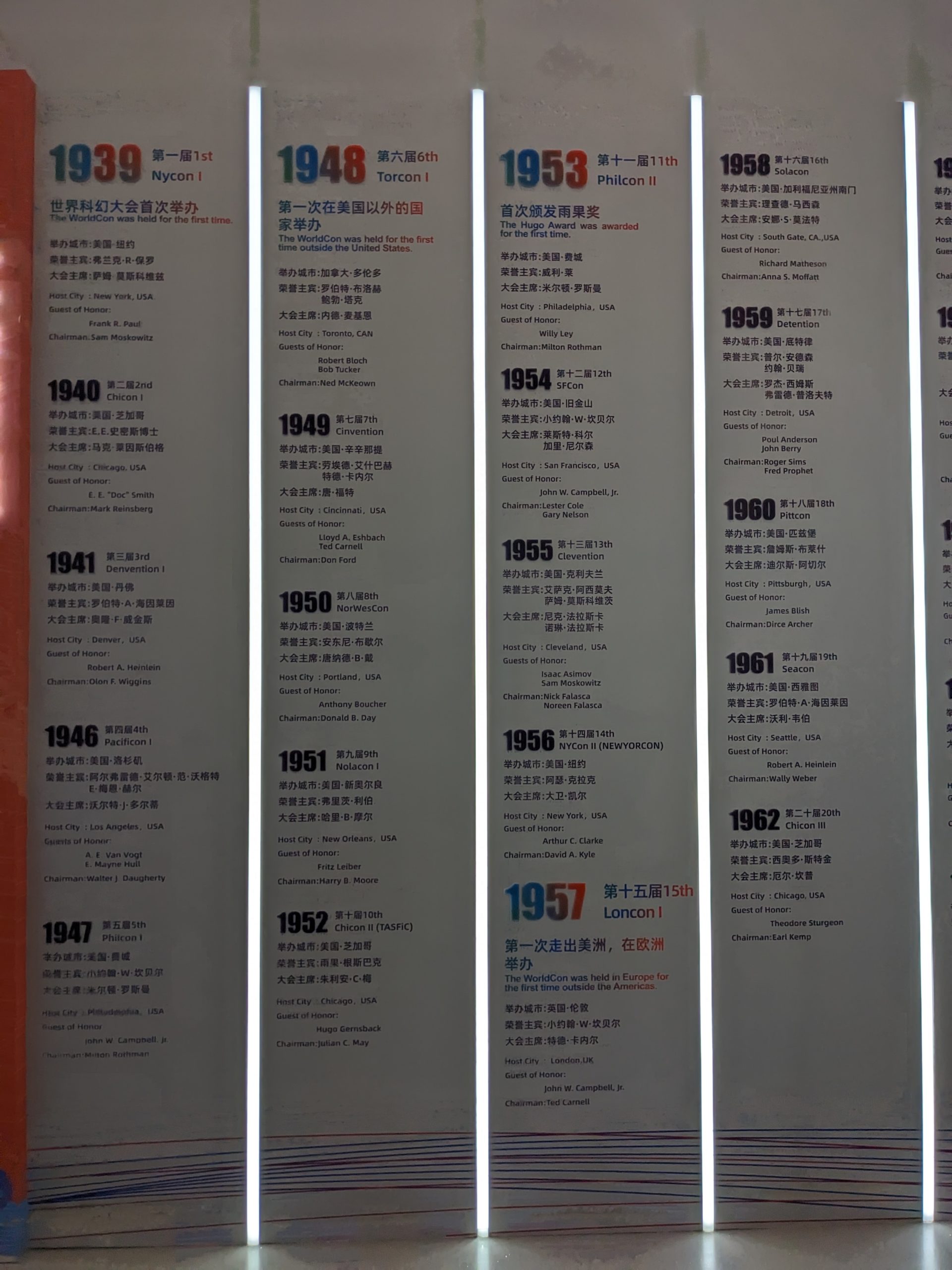

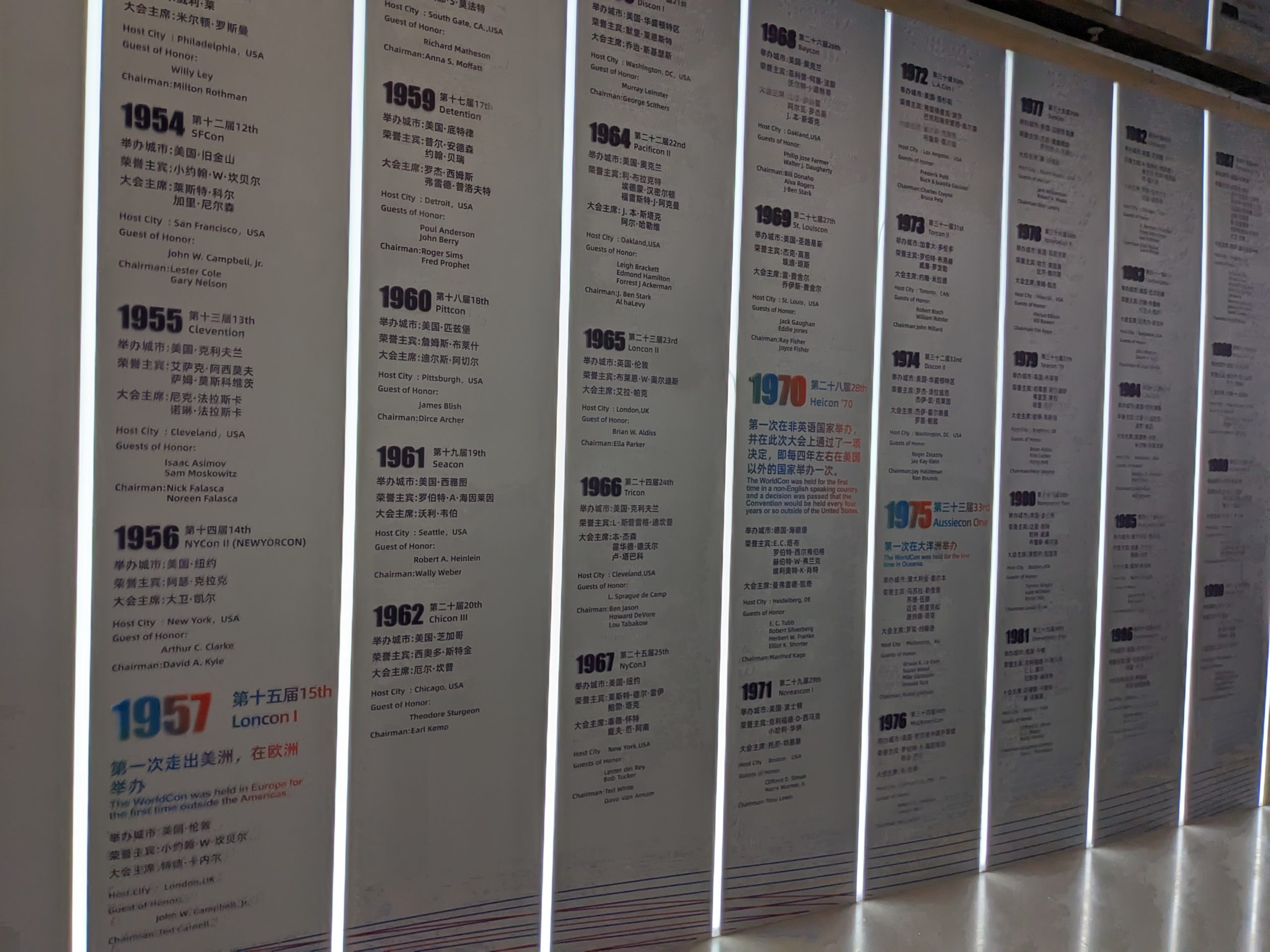

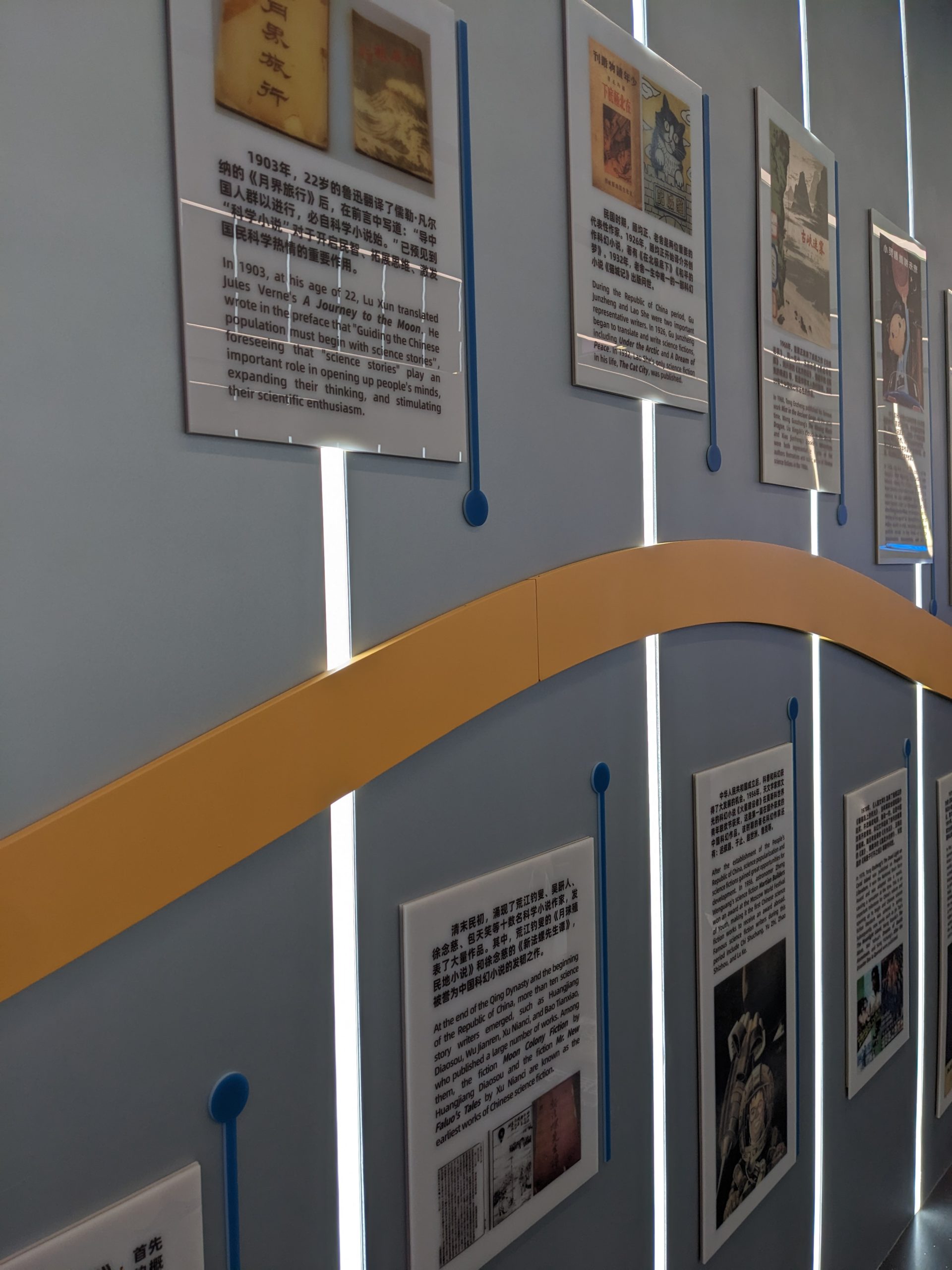

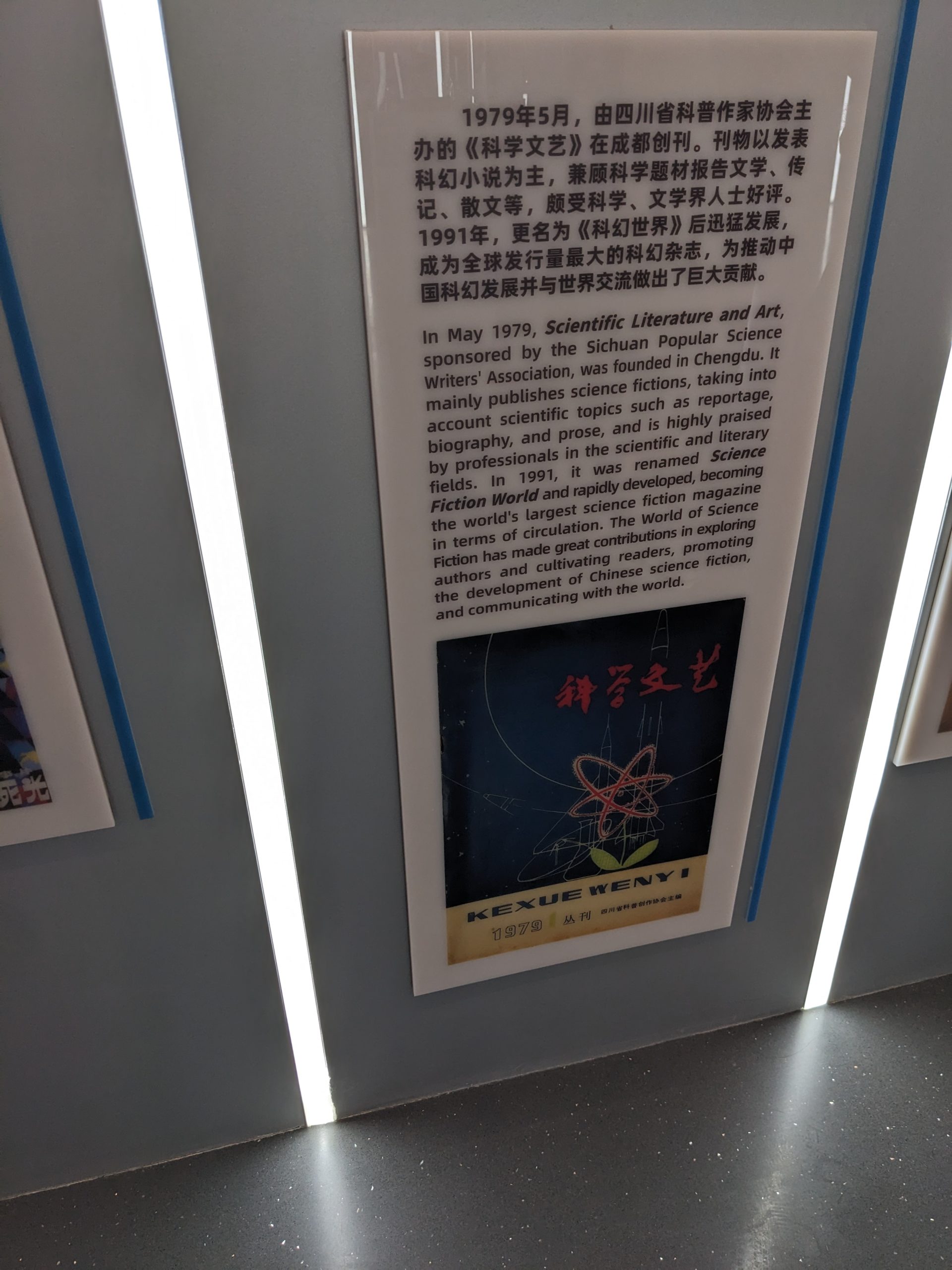

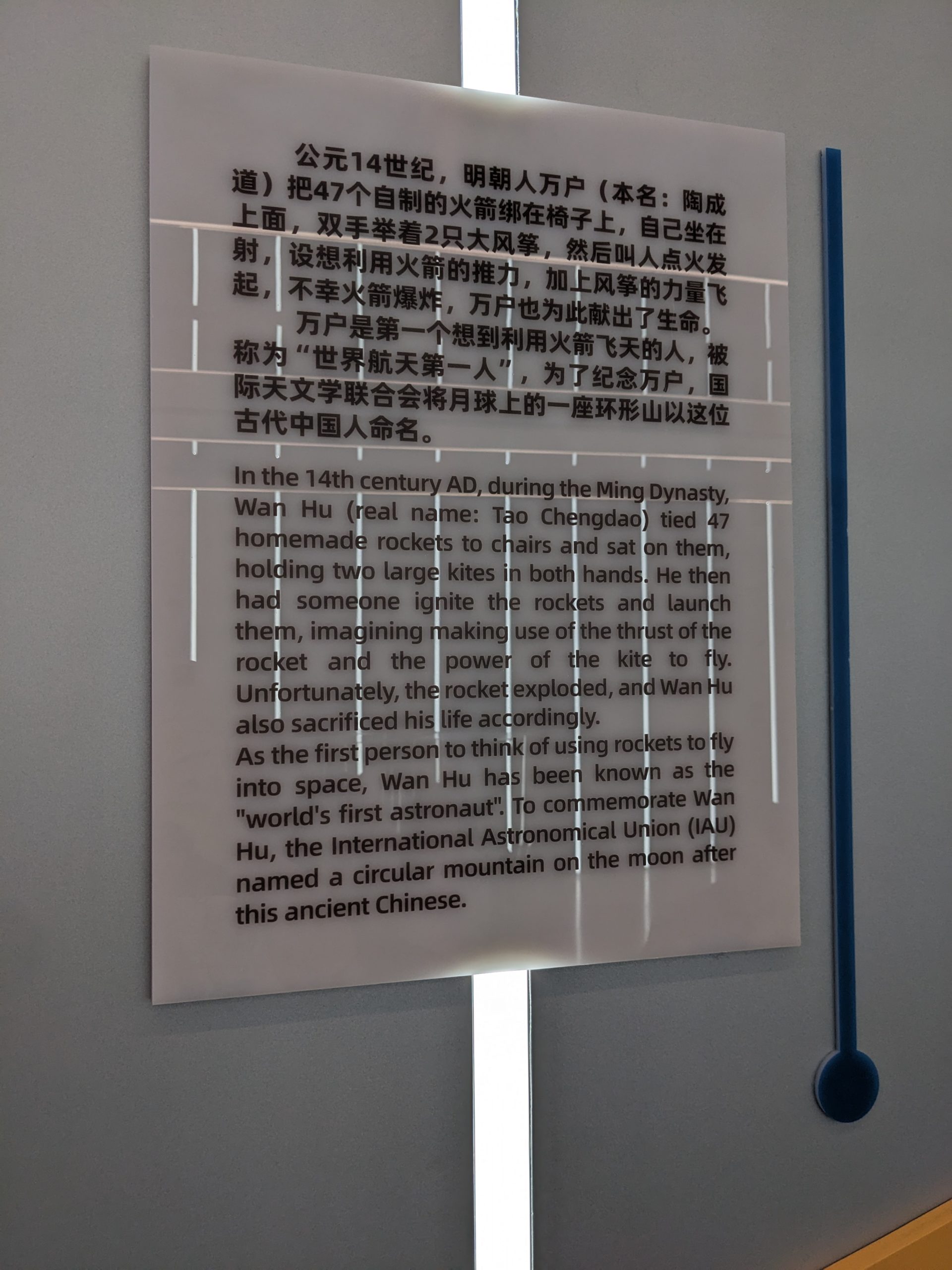

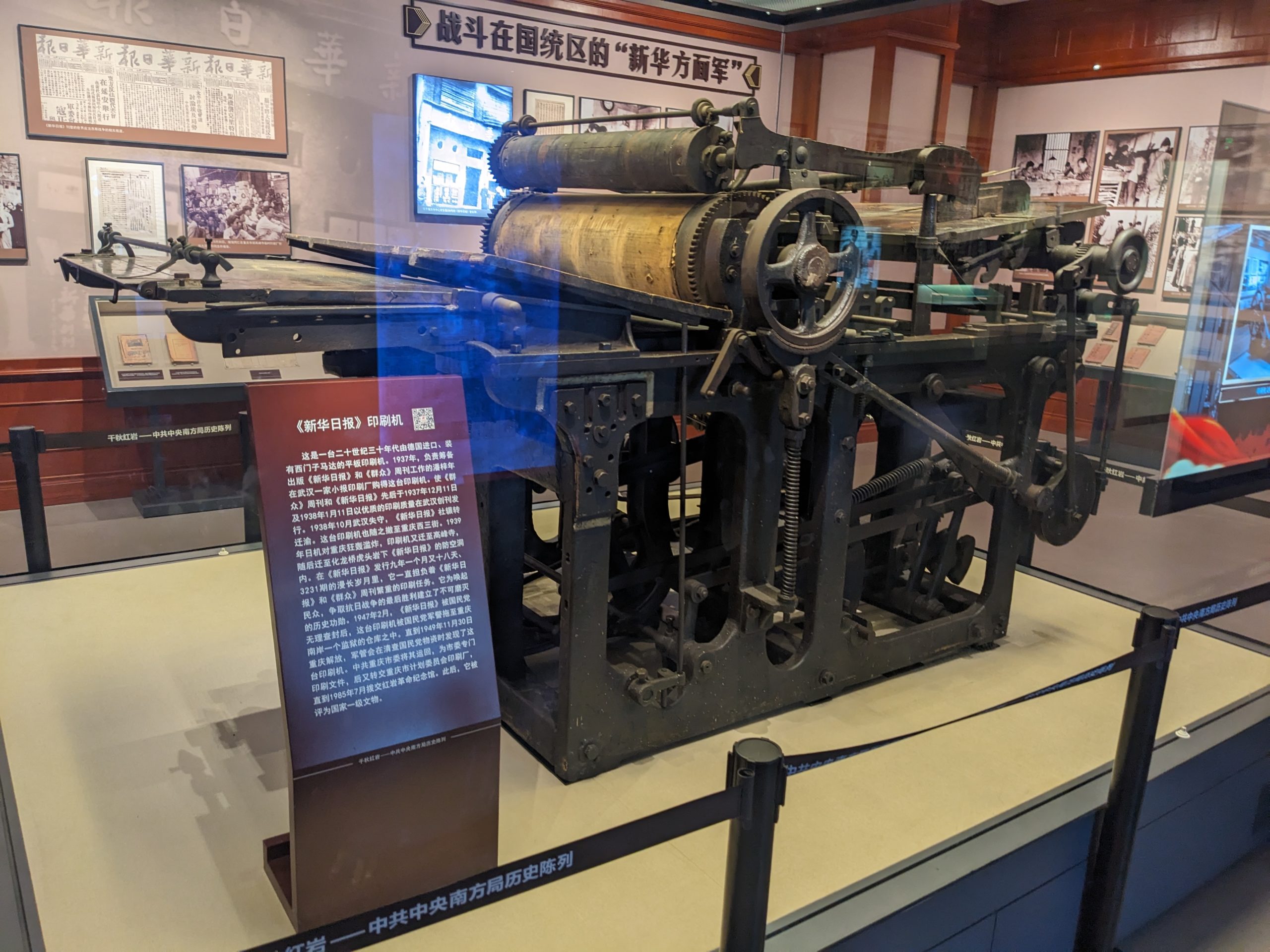

At the entrance to the other hall, which I think they call an "Exhibition Hall", there is some history about Worldcon and about science fiction in China.

One important problem is lunch. There is a small "food court" at the venue but it only offers a few Western fast food choices. I am not excited to have come all the way to China to eat American food but it doesn’t really seem like I had a choice — I don’t want to leave the venue and have to risk my baijiu a second time coming back through the security checkpoint.

The food court has volunteers too. The volunteers listen to your order and then tell the restaurant workers what you wanted. This seems a little weird and subservient at first but I learn it’s because the restaurant workers largely don’t speak English.

I get the black pepper steak sandwich and the cookie because I wanted to maximize calories. It is fine.

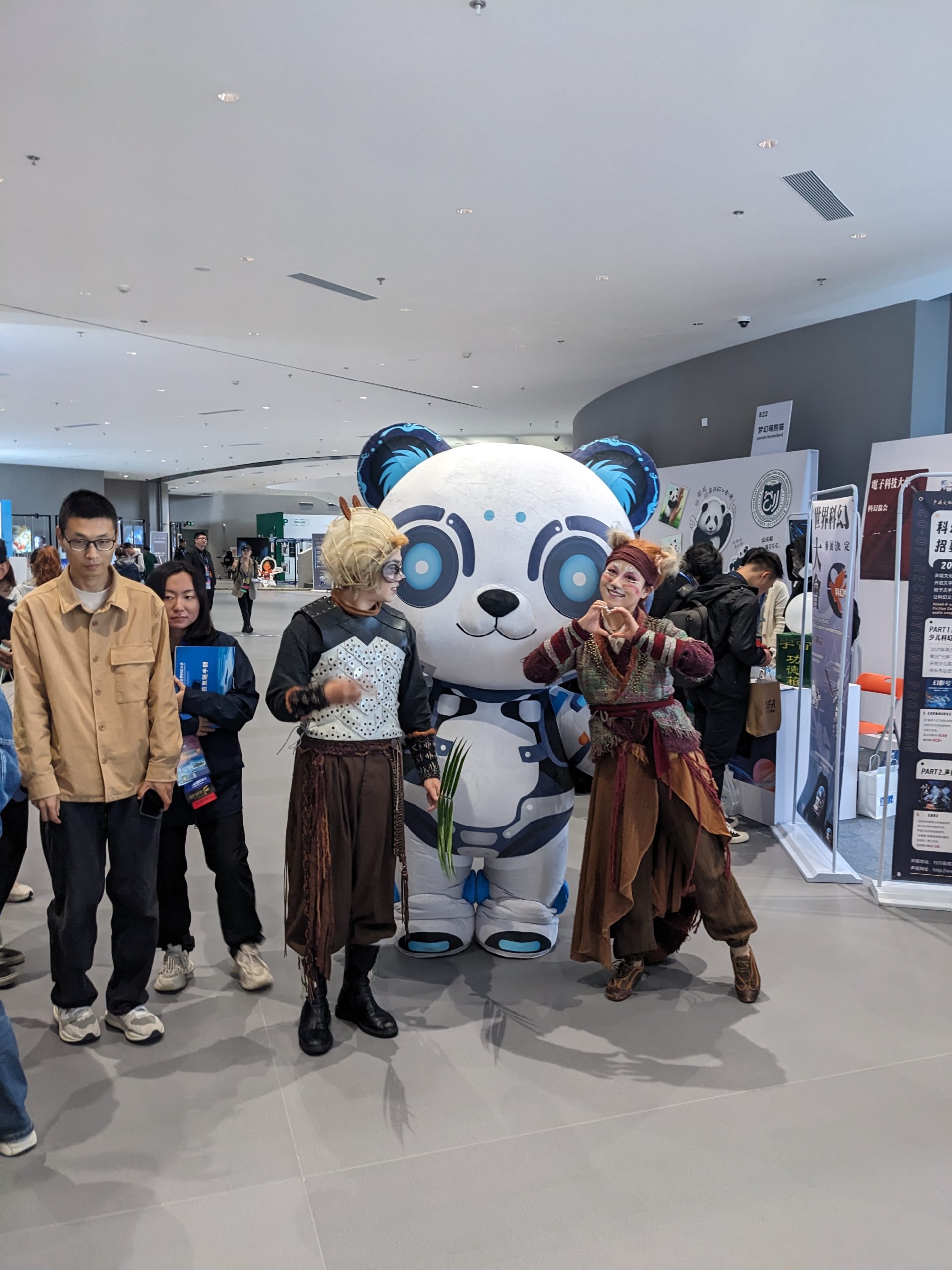

The attendees are almost entirely Chinese. The average age is much younger than at an American convention. Everyone is friendly, particularly the volunteers, who will come up to you at the slightest provocation. I have met a lot of volunteers already and I am struggling to remember which ones are waving because they have already met me and which ones are just being friendly. In the exhibition hall, a gentleman strikes up a conversation with me — he’s Chinese originally but lives in California now, where he is a science fiction author. I hold his things while he tries on a costume — an astronaut outfit from one of the TV shows based on Liu Cixin’s work. Then a TV crew asks to interview me. They are from one of the Chinese networks and they ask a bunch of questions, including what my favorite science fiction is, why I came, and my history with science fiction fandom. I’m not prepared for the experience and later I think poorly of my answers. I wish I could run into them again and give better ones, but of course I never do. (I’ve had a lot of time to think about it since then. Indeed this blog post could be viewed as the "real" answer.)

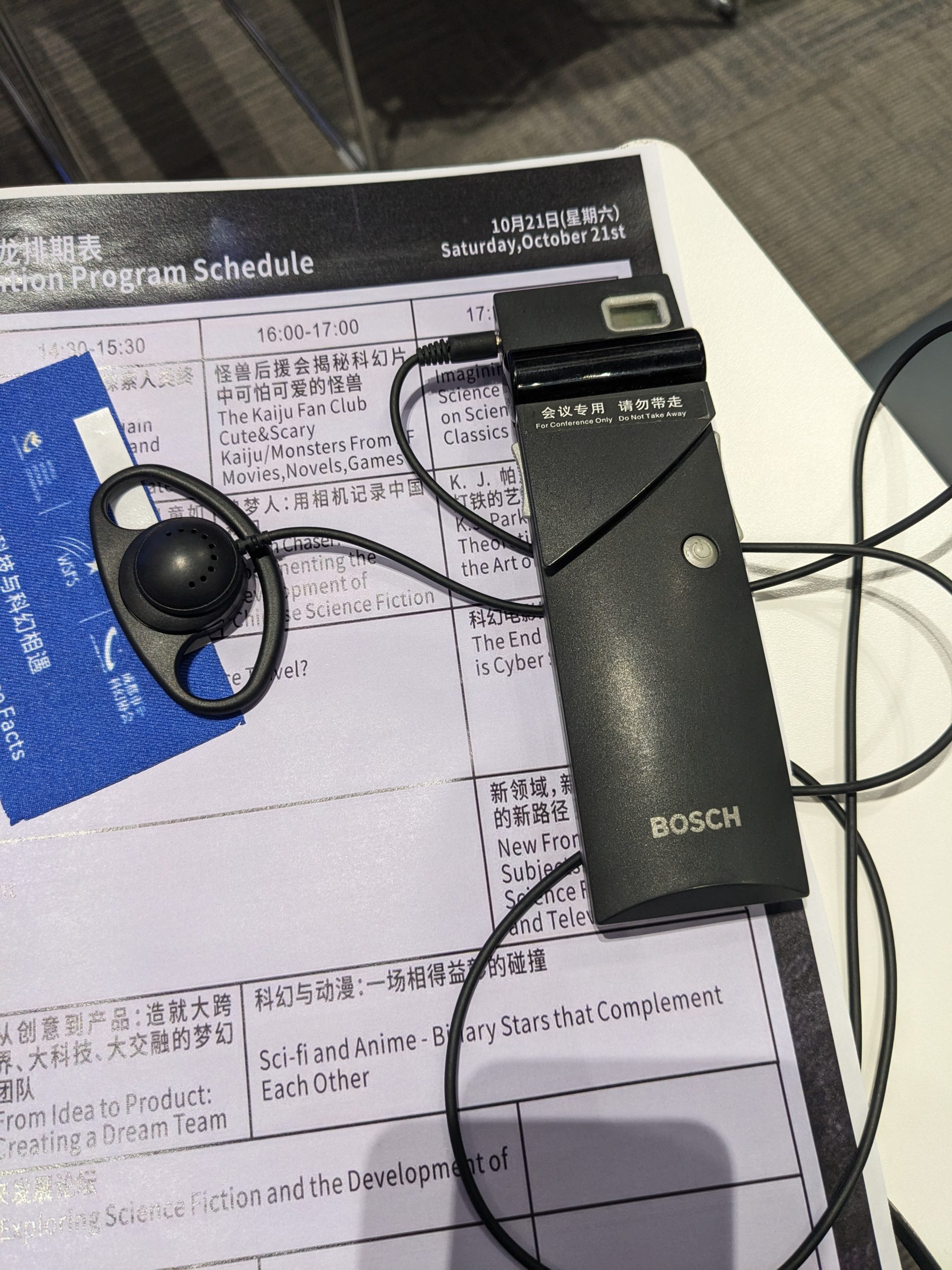

While the convention is clearly pitched at a Chinese audience, there is a visible effort to welcome those few of us who came from abroad to see what "our" Worldcon would look like when translated into Chinese. Panels can be in either Chinese or English, and the panel I go to first has a station outside it with little earpieces. These are for simultaneous translation — some panels have a team of translators in the back. The first panel I attend is in English, so I don’t need one, but many Chinese people use them to hear the panel translated into Chinese. The panel is "Anthropocene and Capitalocene: Threats and Hopes to the Future of Humanity", and it is a firehose — recommendations, opinions, predictions. I come away disagreeing with most of what I heard — in particular one panelist who wrote a story about a city with no people in it, because from his perspective cities are "of course" fundamentally inhuman and not desirous of humans, being messy, unclean animals rather than the cars that cities "truly" run on. This is the kind of nonsense you would expect to hear from someone who lives in Rome. My feeling is that our path to avoiding global catastrophe runs right through increased urbanization, so it feels bad to have the panelists conflate "rural" and "natural" with "ecological". Nevertheless I leave with a short reading list.

An earphone. I take this photo at another panel much later.

The big event of the evening is the opening ceremonies. Not every Chinese attendee got a ticket, but because we are on the One-Hundredth Light Second Plan, we are guaranteed entrance; there are tickets printed right on our badges. There is even a section of seating reserved for us — not too good, sort of the back of orchestra left. There I encounter a group of other international attendees. I sit next to them, although I don’t know any of them yet.

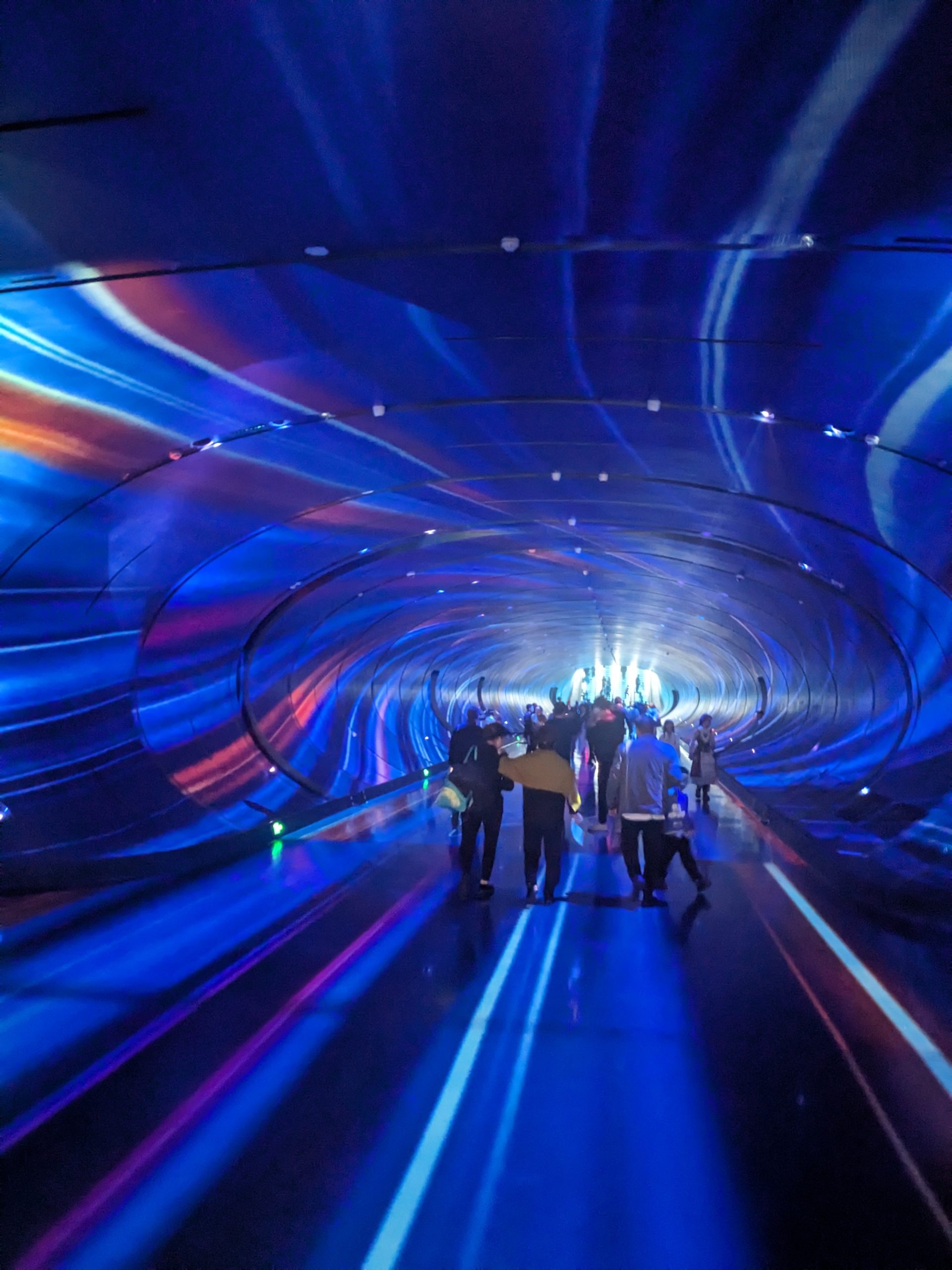

Opening Ceremonies is a great big spectacle. It’s mostly in Chinese but they give us translator earphones on the way in. (Set channel 1 for Chinese, channel 2 for English. Mine seems to cut out unless I hold it at a specific angle.) It includes performances, which you can see at https://www.youtube.com/@chengduworldcon1121. Check out this one for a bit of face-changing opera. There’s a segment where a teacher and two students come onstage to chat with Liu Cixin, and there are speeches from Big Name Fans. They also play the official Promotional Video. Honestly, check it out and tell me you didn’t get a little hype.

A desk is rolled out with a long knife switch, which they pull dramatically to activate the convention or whatever. The final symbol is of course the gavel, which the chair of the Worldcon traditionally bangs to start the convention. They play it straight — no funny sound effects or anything.

Then this happens:

Some young people come onstage and they start to sing a song, before they are surrounded by what looks like the performing arts departments of several schools. They continue the song while backgrounded by some kind of moving light show. The song is called "Meet the Future" and it is the the theme song (!!) of the convention. Verses alternate between Chinese and English but I couldn’t really understand either without the lyrics, which are helpfully projected onstage. (They are mostly omitted from the video.) The venue has it on loop and you will hear it when walking around the grounds for the rest of the convention, so get used to it.

As we file out of the ceremonies, we see that there was some other event happening around in the back. It’s a light show that projects light onto fountains of water to play a movie. I’m nervous about missing the shuttle, especially how tired I am, so I don’t stay for all of it.

[FIXME: something wrong with the videos?]

In the front, the fountain/pool has been rigged to have music and light synchronized and it is also pleasant to watch.

I get on the shuttle. There are some other international attendees, including many of the ones I sat with. I start to make friends with them — I guess some of them might know each other because they have already been in the area for a few days, for example to take advantage of the free city tour and attractions that the convention organized on the days before the convention, but there are introductions all around. We are what Yi-Sheng describes as his "wolf pack" for the convention — instant friends and mini-family, united by the fact that we are all not from around here. We are all lodging in the same hotel so we see each other regularly at breakfast and on the way to and from the convention. Additionally, it’s handy to be able to see someone around the convention and be sure you can speak English with them. (Though some of us, for example Melissa, speak Mandarin fluently, so I can’t say that none of us speak Chinese.)

I’m exhausted by the time we get back to the hotel, but overall my impressions of the event are quite positive.

Thursday I don’t even try to take the shuttle. Instead, after breakfast I set out to find another SIM card (see above) and then take the tram to the venue, or at least near-ish to the venue. On the way in I am careful to keep an eye out for nearby food options because I will be damned if I flew all the way to China to eat Subway. All the same, I’m careful not to bring baijiu so I can leave freely.

There are some kiosks selling snacks, including these baozi. I am able to mostly get by in Chinese here. The last one is Sichuan flavored somehow, and it is delicious! Because I had business to conduct, it’s about lunchtime when I get to the venue so this will be enough to tide me over until dinner. Nevertheless I ask at information if there is really no other dining options in the venue. The program book says something about a "Nebula Camp" containing a variety of food trucks which is supposed to be relatively close to the venue so I ask about that. It seems that it isn’t open although the volunteer cannot tell me exactly why. In the end, my guess is that it was part of the museum area that wasn’t finished in time, and won’t be for the duration of the convention.

I have a strict limit, born of years of experience, not to see too many panels while at this kind of event, because they start to drag and the parts of the convention I enjoy the most are usually elsewhere. I think about one a day is good. I have a couple of hours to kill until the first panel I want to see that day. I intend to go back to one of the pictures I saw while wandering around and take a picture. As I am coming up the stairs to look for it, I hear someone say, "Excuse me!" It’s a young lady named Yang. She’s a journalist who lives in Beijing who came to cover the convention, and she wants to interview me. Like the interview yesterday, it feels flattering that someone thinks my opinions are worth listening to (I’m famous!) so I agree. We have quite a far-ranging conversation that covers a lot of topics and it’s quite enjoyable, not just because I get to hold forth while a young lady listens attentively. Because I have had some time to think about some of the questions, I have some better answers. (What’s your favorite science fiction work? Maybe Accelerando by Charles Stross.) At the end, we exchange contacts. She doesn’t seem to mind that someone else has gotten to me first. While I will only do these two interviews at Worldcon, one member of our "wolf pack" ends up doing something like seven.

It seems that us "foreigners" (as we are sometimes referred to by Chinese nationals) are quite a sight — from time to time a Chinese person will come up to you and ask if they can take a picture with you. Because it is novel to me, I think it’s hilarious, but I can imagine it wearing on someone who has spent a lot of time in China.

The panel I see that day is about a magazine called Galaxy’s Edge. I don’t know much about it, but from what I understand in the panel, it seems like it’s the name of two "sister" publications, one based in China and the other in the US, and each will publish stories from the other (in translation, of course). This sounds really interesting and it also goes on my reading list. (See here for more details that I looked up later.) The panelists include the editors for both "sides" of the publication. This is my first opportunity to see how the translation works — some panelists speak in Chinese, and others in English, and many attendees use the earphones to listen to the language they don’t understand, so the translators are converting in both directions on the fly.

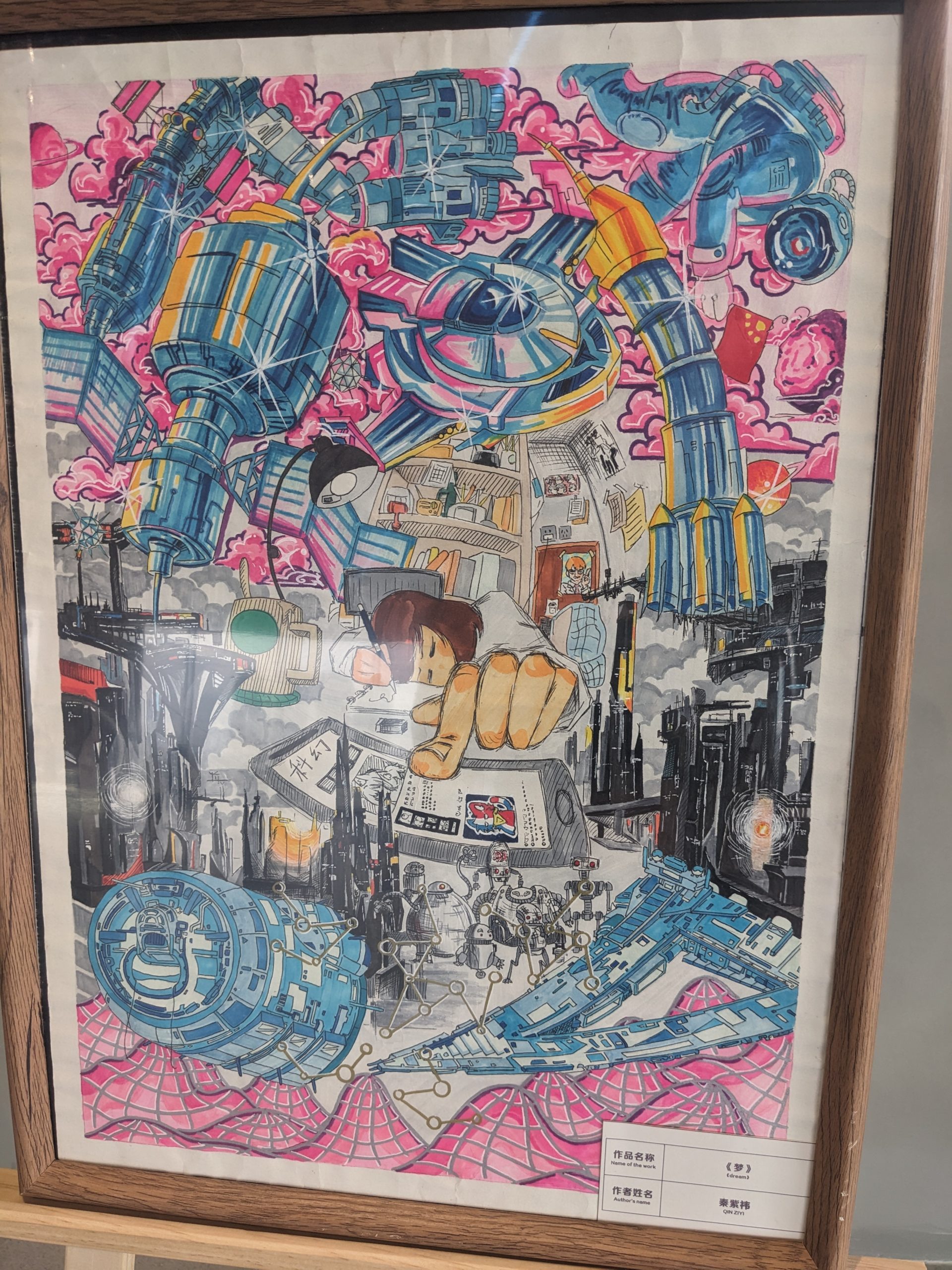

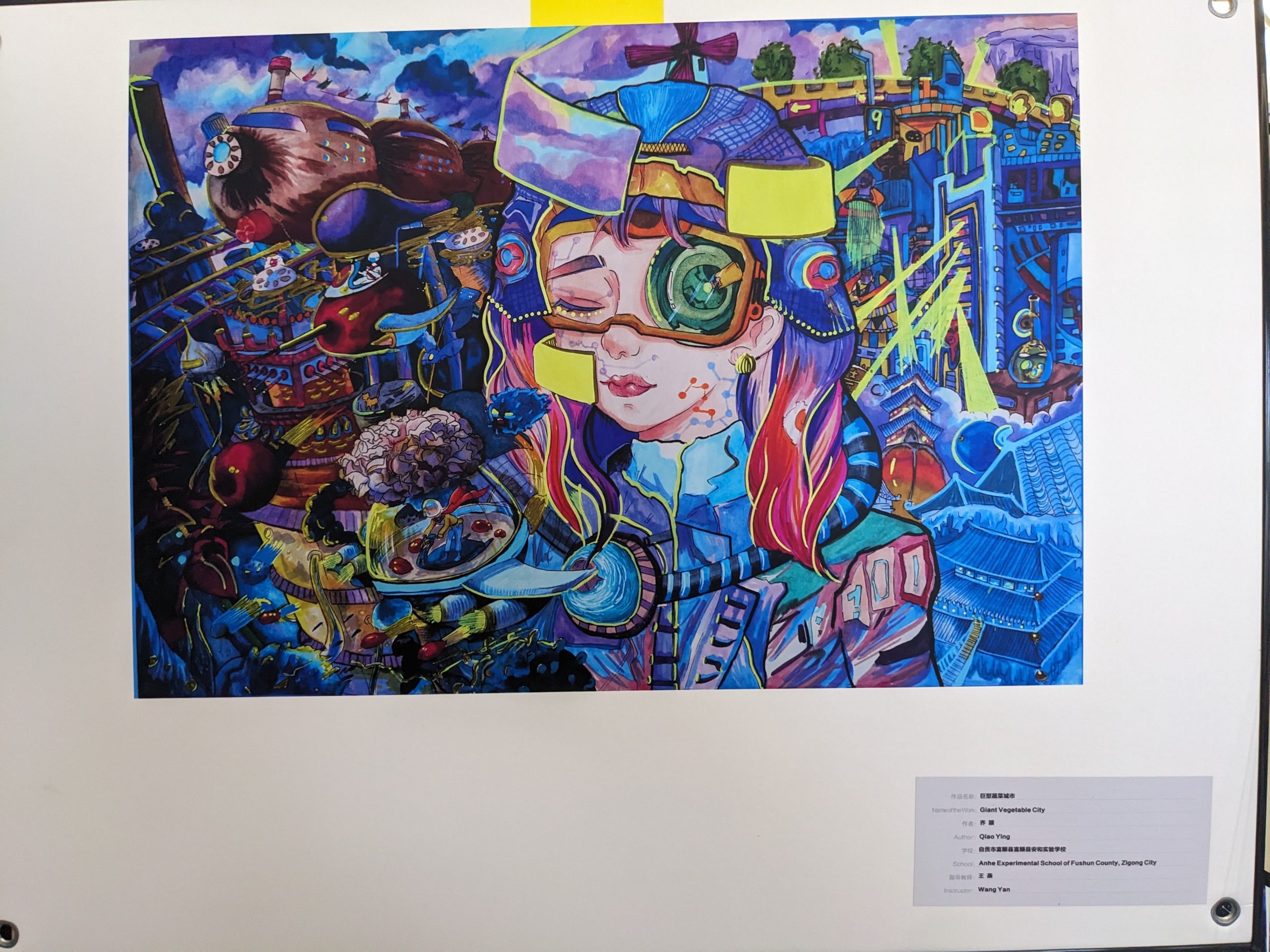

This is the picture I wanted to get a photo of. Unlike other conventions, there isn’t a separate "art show" with just artwork — instead, there are lots of art pieces arranged in three or four clusters in the venue. There is also no "silent auction" that causes pieces to be sold. (Is this a cultural difference related to different economic structures? No idea.) One cluster shows large prints of cover art from Science Fiction World; another shows art by well-known Chinese artists (that, of course, I have never heard of). I think one cluster is art by schoolchildren. I’m not sure about this piece — maybe an older student? — but something about it resonates for me.

Yang has proposed that while she is in Chengdu she is going to take advantage of the situation to try to get some local food, particularly hot pot, and would I be interested in going? Of course I would. She suggests that I can invite some of my foreign friends as well. Also, by the way, she asks, this word "foreign", "foreigner" — is it an OK word to use? Is it polite? The term’s relative in Chinese, laowai, is one that I had encountered when studying Chinese back in college, although I don’t remember any more what Professor Shen said about it. I tell her that I personally don’t find the term offensive, just a little confusing because from my point of view, I was surrounded by foreigners! Of course, my specific situation is a little complicated because of my time in Cameroon. There, the term they call "foreigners" is le blanc, "the white" or "the white one", or the equivalent in a local language (ours was something like nduk), and being reduced to this attribute never feels good. By comparison, "foreigner" seems fine. (A Cameroonian might also use the term occidental, "Western"/"Westerner", because that tends to be the most salient divide in that context. However, our "wolf pack" includes an Indonesian and a Singaporean, so "Westerner" wouldn’t be appropriate.) The whole question strikes me as uniquely Chinese — both using the word, but then also the focus on whether to use it was polite. A Cameroonian would never wonder if the term was polite!

By now I am on WeChat but don’t yet have the contact information of the other foreigners, but milling about aimlessly they are easy to pick out, and as I encounter them I tell them about the plan to get hot pot with Yang. In the end, I get Sean, Silvana and Leadie interested. Around 5:30 we leave; we take one of the free shuttles from the venue to the closest subway station. We are aboveground at a bus shelter, which I want to take a picture of, but there are two Chinese women sitting in front of it. I don’t want to include them in the picture without permission, so I start to stammer out in Chinese, "Excuse me… can I… photo…". Abruptly, one says "You can speak English." I am grateful but maybe just a little chagrined.

Did I mention about the marketing the convention did?

From the subway station we take taxis to the restaurant. Actually there’s a whole strip of eateries and businesses:

Leadie, Sean and Silvana were in the other taxi; we find them around the corner. We enter the restaurant for our first hot pot experience.

First, you have to be dressed for the occasion. They give you an apron to prevent your clothes from getting dirty. For those with glasses, they give a microfiber cloth so you can clean them afterwards.

They also give you a little plastic bag to put your phone in, so you don’t get it greasy (or spicy?). Mercifully, the bathroom is fully stocked with soap.

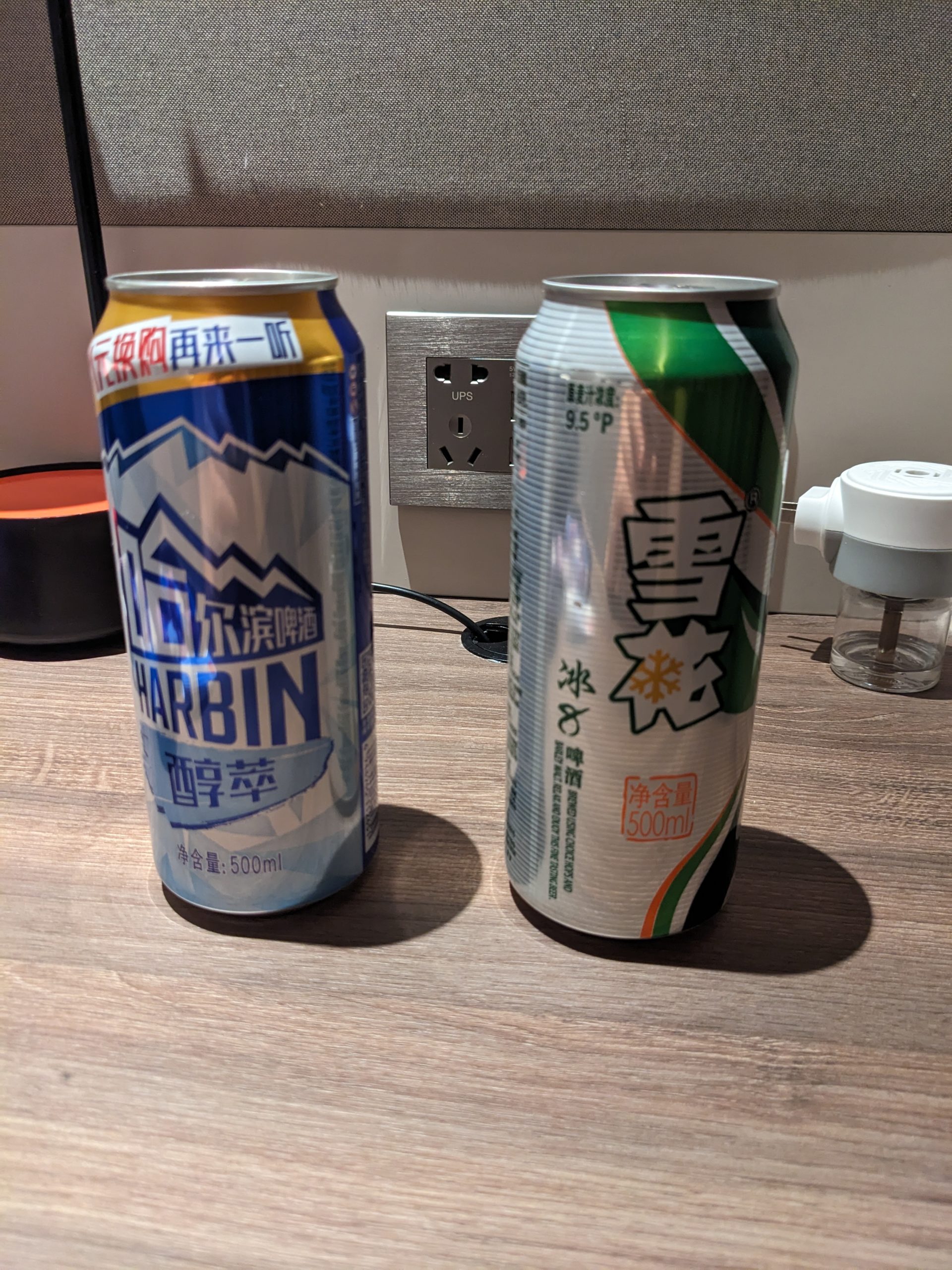

I get a local beer. It’s totally unremarkable!

They bring out some appetizers and a timer. The timer is how long they are allowed to take to get the broth ready. If it takes longer than 20 minutes, you get more free appetizers. (They were well under 20 minutes.)

This pudding was amazing and I didn’t want to eat it all before the spicy food started to happen.

We opted to have some part of the pot be spicy and one be less so.

We eat a lot. Different kinds of food need different amounts of time in the boiling soup.

I think this is rumen, i.e. beef stomach.

Afterwards, the restaurant staff ask if we liked everything, and if we had any feedback about their service or any advice on how to improve. It feels obsequious to me, like if it were America, I would have assumed they were fishing for a tip, but Yang says it’s not too unusual.

Afterwards, we decide to stroll through the "snack street". Apparently Yang chose her hotel location according to where the good food options were. These fruits are coated with some kind of crunchy sugar coating and they are all delicious. (Thanks to I think Sean for the second picture and Silvana for the third, fourth and fifth.)

Once we get to the end of the street, we take a taxi back to the hotel. (Silvana has figured out how to use the taxi app.) We pass a variety of interesting-looking shops — a place called Urbrew, which (unless I miss my guess!) is a local brewery; a place called "Frog and Fish Lab". I want to check out more of these places!… assuming I can find them again on the map.

Friday my stomach does not feel well. I spend the morning fielding a phone call with Peter, which normally I would decline while I was travelling, but since I was hesitant to leave the hotel room and its bathroom for a while, it was fine. By the time I finally leave the room, I have definitely missed the shuttle to the venue. By now I’m familiar with the route and I walk it.

There is lots of interesting art, much of it sci-fi, along the way.

On the way in, passing where I collected my badge, I see this unassuming sign which seems to signal a restaurant. It seems worth considering…

… but the "wolf pack" instead decides to go to a different restaurant, which isn’t too far although nobody is exactly sure how to get there. Yi-Sheng is able to ask directions of one of the locals in Mandarin, although her response is not totally clear. "She said we should see a big balloon…?"

On the way, I chat with Sophia. She and her husband Tim live in Portland now. She asks where I’m from.

"New York," I say.

"Oh, really?" she says. "I grew up in New York."

"Oh, really? What part?" I ask.

"Brooklyn," she says.

"Oh, really? What part of Brooklyn?"

"Midwood," she says.

"Oh, really? What part of Midwood?"

She gives me a funny look before I explain that actually where I live now is this street and this avenue, and I grew up not too far away on that street and that avenue. It turns out she grew up just a few blocks from here. The high school she went to is on the way to my parents’ house! It’s a small world.

We pass some interesting sculptures.

Eventually we find our way there. Sure enough, there is a big inflatable "moon".

There is a restaurant on the corner. The food is quite good. (Thanks Yi-Sheng and Sophia, respectively, for the last two pictures.)

I try to ask about these desserts and I think the person making them explains that they are for the convention although I am not exactly sure what they are for.

There are also a handful of little stalls here. They seem like they are affiliated with the convention, but we are a good twenty minutes’ walk from the venue and it isn’t clear what they are doing here. Indeed, many of the vendors standing behind them are sleeping.

Sophia and Tim get some of these adorable little dessert things. I get one. The woman who is selling them gives us these little skewers to eat it with but I am not sure how to get the food item onto the skewers. The vendor demonstrates and holds it out for me to see. "Oh!" I say. "Can I take a picture of you? My girlfriend wants to see all the food I eat." The woman nods her assent, but after a second, she says "… maybe it would be better if I take your picture." Like, maybe it would be better for you not to send pictures of strange women to your girlfriend. We all think this is hilarious. "Some things really cross cultural boundaries," says Tim.

We bid farewell to the moon and its alley and go back to the convention.

There certainly more people today than there were in previous days. You can probably get a sense of the demographics of the event from these pictures. The gender balance is not as skewed as at an American convention, and there are lots of families, especially with young kids. Science fiction is for some of these people not just a niche nerd thing, but a fun genre for the whole family. I always think of science fiction fandom as countercultural and struggle to square that with the fact that a lot of "mainstream" media is sci-fi in some way, so this is a very different perspective. How come science fiction fandom is no longer a thriving subculture in the United States, but ten thousand attendees came to Chengdu? One person mentions to me that we tend to see more science fiction in times of technological revolution and dramatic social change, and it’s easy to imagine that there’s a lot more of that in China than in the US right now. Or does it have to do with the mainstreamization of the genre in both places?

It may not be obvious but in the middle-back of this photo is a line of people. This line goes forward up a ramp and in to the convention hall through a winding maze of cordons to get autographs from Liu Cixin.

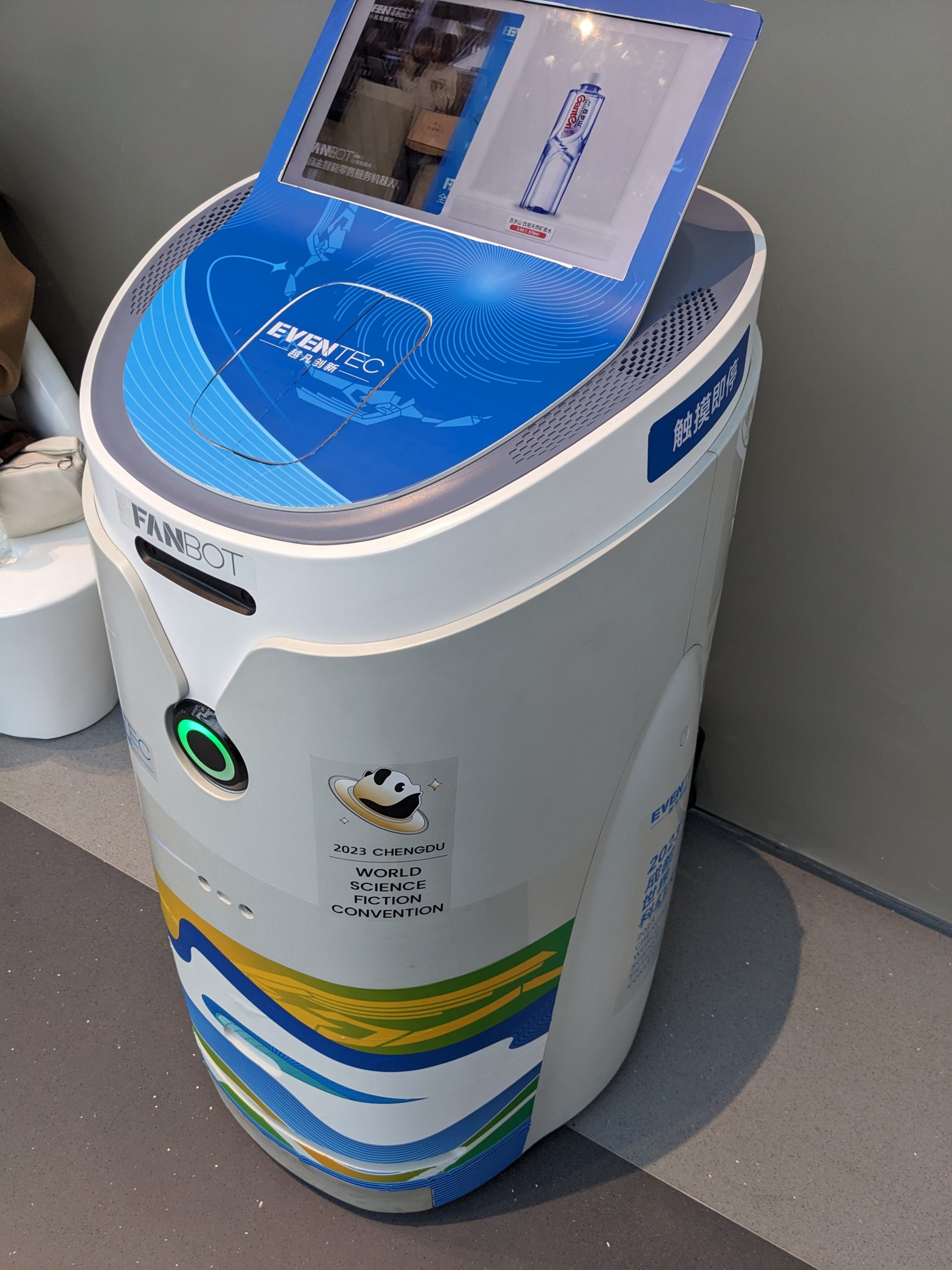

There are a few vending machines around the venue. They all work on Alipay/WeChat — you scan a code with your phone and get a menu, and once you’ve selected something, you pay digitally — cash not accepted. By now I have Alipay set up so I am interested in giving it a shot. Some are wheeled and amble around their floors. (One keeps walking away when I try to make a purchase.) The kind in the second picture are near the food court. I order something suspiciously like a Fanta.

The only panel I try to attend on Friday is "Mini-game: Sci-fi Turtle Soup". I have no idea what that means. Unfortunately, I discover that this panel is going to only be in Chinese, and it doesn’t have translation. Some of the "wolf pack" have discovered that if you insist, the volunteers can call an interpreter for you, who will sit behind you and whisper to you what’s going on in the panel. This seems very intimate to me so I pass for now. It turns out that the other foreigners are also unable to attend the panels they want, either because they are full or because they are not translated. This is going to be a theme for the remainder of the convention. The bilingual-ness of the convention, which seemed so thoughtful before, is maybe turning out to be a little bit less complete than desired. Instead I head to the food court, where some people are hanging out and chatting. A friend of a friend there is named Annie, who works for Huawei and is promoting the panel she is organizing tomorrow morning. The title is "When Technology Meets Science Fiction" and Nnedi Okorafor will be there.

My stomach is still a bit uneasy and I spend a lot of time looking for a toilet. While there generally seem to be enough bathrooms, at least in terms of urinals, the toilets seem to be occupied. (I later learn that some people are using the toilet stalls to smoke, to try to get around the venue’s no-smoking policy.) Sometimes I find an empty stall only to find tha it’s a squat toilet — each bathroom has some of each, "Western" toilets and squat (a.k.a. "Turkish") toilets, with an icon on the stall door to tell you what you are about to find. They also all have the design where the latch mechanism connects to an indicator on the outside of the door showing red "occupied"/green "free". I am really hoping for a Western toilet at this point — while I would be willing to try a squat toilet, being at a convention venue and potentially with diarrhea is not that circumstance. I stalk from bathroom to bathroom, glancing at the doors in each for both the right icon and the green "free" marker until I find a stall where I can evacuate in peace.

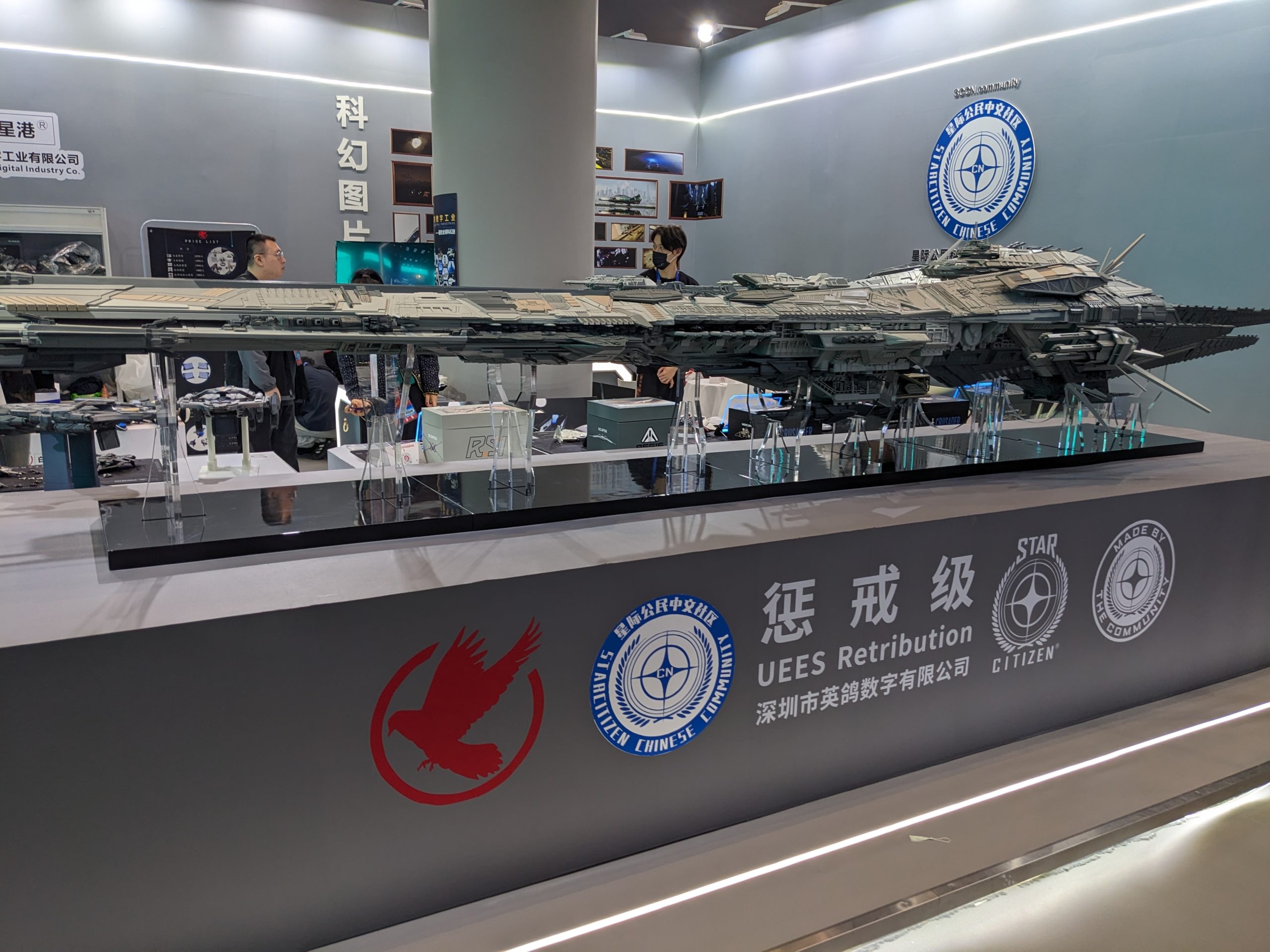

One vendor is in the business of constructing models, for example for television or movie production.

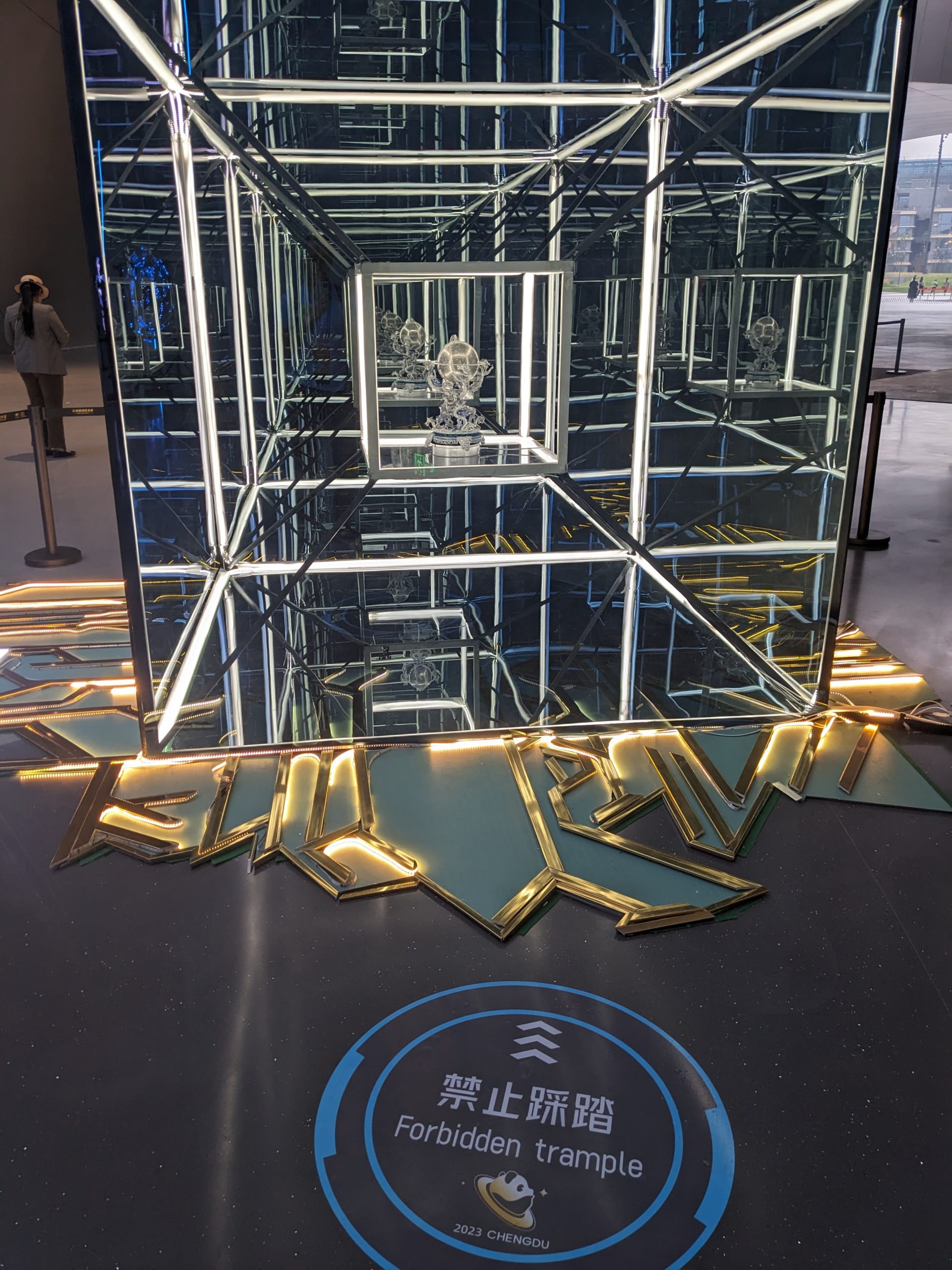

One of the displays in the main hall. "Forbidden trample" shows up here and there in the convention to discourage putting weight on electrical equipment.

There’s nothing special going on after the convention that evening. I am trying to get some people to come with me to Urbrew but it seems that people mostly want to go to bed or hang out at the hotel restaurant. Some of the foreigners are talking about taking a taxi back to the hotel, but instead they look confused and after a few minutes, convention staff summon a shuttle just for them. I decide that I want to see if I can find one of the Citibike-looking things I’ve seen around and get a little bicycling in. Unfortunately I can’t find one. (In the end, I don’t get to ride a bicycle in China at all.) Instead I opt to take the tram to save a little time.

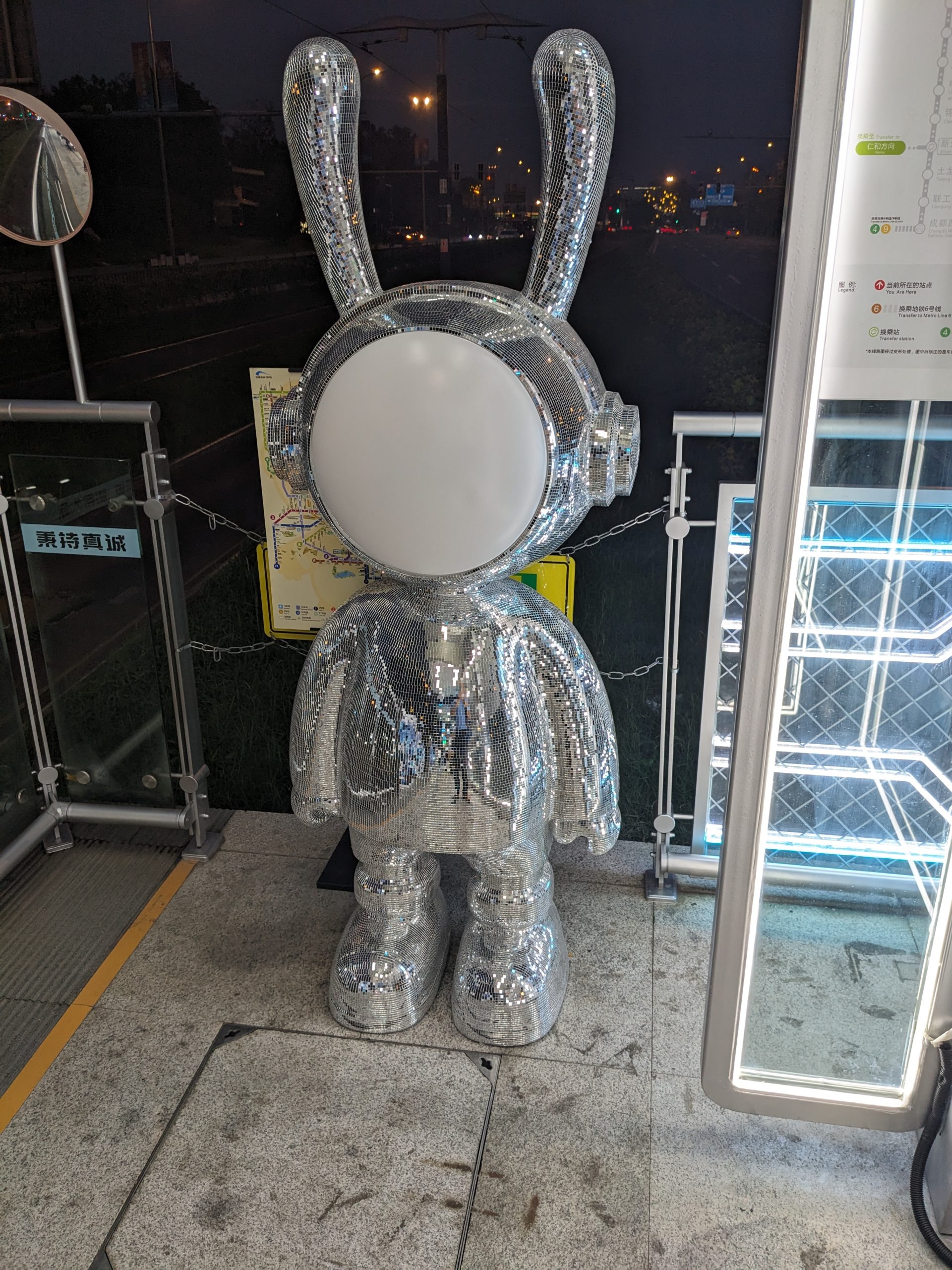

Some of the decor at the tram station.

I pass this striking sign after getting off the tram. For a moment I hesitate before taking a picture (is this going to get me thrown in Soviet prison?) but nobody seems that interested in it so I take a picture. I love propaganda! Google translates it as "Seek happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation!"

By the time I get back to the hotel, dinner has mostly been eaten. We have a fun conversation about Chinese sci-fi, about which Melissa is extremely knowledgeable — she’s a professor of some kind of Chinese literature at a university in California. (I take down more names for my reading list.) In an earlier conversation, some of these people took a "Can I just say? I don’t like Liu Cixin! I don’t like his work!" stance, but in this one, there’s a much more mellow "Well, he’s kind of the dean of Chinese sci-fi, and I don’t think he likes it any more than I do, but he’s doing his best to manage that fame". Melissa points out some interesting motifs of Three-Body Problem, such as the symmetry between the reference to "Silent Spring" in the early part of the book and a climactic scene at the end of the book featuring locusts. It’s a great conversation and very much the sort of reason I came.

Unable to convince anyone to go to the brewery, I content myself with a couple of local beers from the convenience store downstairs. They have pop-tabs like a can of sardines. "Enjoy this fine tasting beer."

Saturday I am more or less back to normal. After another wholesome breakfast, I head down to the shuttle, and I just miss it, but this time I approach the convention staff and they radio in to the shuttle, which is only a half a block away. I, and another convention attendee who came down in the same elevator I did, run to catch up and are able to board. By now, everyone in the shuttle is an old friend, and I introduce everyone to the new person, who is from Shanghai.

It’s sunny today and I joke that nobody knows what to do about it. It’s the first day, and maybe the only day of my trip, where the haze and fog clear.

I have no idea what this robot is.

By this point in the convention, it’s increasingly clear that the majority of panels will not be translated, and a lot of the really interesting ones in particular are not really available to us foreigners. The program guide doesn’t really indicate which panels might be understandable, so you have to guess. (One of the volunteers even suggests to me that I look at the panelists’ names — if they seem like Chinese names, the panel will probably be in Chinese.) The program guide itself is not as helpful as you might want — the titles aren’t always clear, for example I am baffled by "Follow one’s Dream as a Horse", which turns out to be a presentation of a group of high school students who have published their own science fiction magazine. The only additional context is the "Agenda Topics" for each panel, which are quite abstract indeed.

Since the panels I thought I was interested in turn out to be already full or not available in English, I have a lot of time on my hands. For lack of anything better to do, I decide to go to the panel Annie was talking about yesterday, because she explicitly said there would be translation. I find my way to a part of the venue I hadn’t been in before and was greeted at the door with a earpiece and a bottle of water. They invite me to sit in the front row, but then I would feel bad if I didn’t pay attention, so I choose a seat on the far right, one row back.

The panel is a strange one. The panelists seem to be Nnedi Okorafor and a bunch of people associated with Huawei. Each presenter, by turns, stands up and gives a brief presentation on "their" topic. The non-Okorafor presenters seem involved with some kind of AI topic — a new model that Huawei hed developed. It seems that there was some kind of competition where people tried to get the LLM to generate the most striking artwork by trying different prompts and this panel is also the presentation ceremony for the winners, who each come up on stage and are handed some kind of award. The winners are all men. There’s an "interview" section where the emcee asks presenters questions — Nnedi Okorafor in English about science fiction and Africafuturism, the other panelists about AI and LLMs. I can’t really follow the translated answers, or maybe they are content-free in their original languages as well. The cognitive whiplash continues through Q&A, where attendees stand up and either ask questions of the Huawei presenters that sound like recruiting sweet-talk, or Nnedi Okorafor about gender imbalances in science fiction. It’s almost like two panels got glued together by mistake, but on balance, it’s much more like a Huawei advertisement than a convention panel. Maybe Huawei supported the convention somehow and got to participate in a panel? Perhaps they are even responsible for Nnedi Okorafor’s attendance at the convention? I don’t get it. It’s a double-long panel but I tough it out as best I can.

Afterwards it’s lunch time. I decide to check out the "Energy Point for Sci-Fi Fans", since it’s not too far and the price seems convenient. It’s a bit of a strange arrangement, where the shrubbery blocks lines of sight so you don’t really know what you’re walking into until you find yourself on a patio in front of a restaurant. I am greeted at the front desk and the maitresse d’ takes me to the line — it’s more like a canteen than a restaurant — and busses my table past each station, offering me a little of each, to which I enthusiastically consent. The arrangement seems targeted at Chinese attendees — they don’t have any silverware besides chopsticks. Still, the food looks OK. I text the foreigners about it and a few minutes later Carli, who sat at the Huawei panel with me, sits down next to me, guided firmly by the same maitresse d’, who I assume concluded that the foreigners would be happy to have company. We have a far-reaching conversation about technology, colonialism, Chinese society — another fun conversation. Carli is Swiss but married a Chinese national and has spent a lot of time in China. Despite this, he is mostly a homebody and hasn’t travelled as much except for China. We have a laugh comparing attitudes about travel, since mine are much like his except that I feel as intimidated and overwhelmed about being in China as he does about being everywhere else.

I order this "kiwi soda" on the way out. The bartender makes the drink with ice, which gives me a scare since I had read to try to avoid it, in case it was made with tap water, which is not typically safe to drink, but in the end it was fine. Of course, I have to finish it before I get back to the security check at the venue.

I notice some kiosks off to the side as you come in the venue. I check them out and they have this interesting lychee soda.

One outstanding problem is what to do with the rest of my time at the convention. The panels seem mostly like a bust, and I’ve walked past all the vendor tables and "exhibition hall" booths already. There’s no gaming room as there might be at another Worldcon, nor anything like a film room or con suite, and I’m unable to converse with most of the people around me. For a while, I try just standing in the venue’s "grand hall" near the entrance and to simply see what happens. Maybe someone will interview me or ask to take my picture? But it seems like we are late enough in the convention that nobody wants to talk to a foreigner any more. Still, there is some good people-watching, and it becomes a safe default action when I don’t know how to pass the time for the remainder of the convention.

There are a variety of groups here on what appears to be a school field trip. That’s crazy! Imagine going to a convention for a school trip!

There’s this Boston Robotics robot dog thing and it seems to be attracting a lot of attention especially from kids.

I entertain myself for a little while trying to get the perfect shot of the clever way the young lady is operating the device.

Although there isn’t much in the way of cosplay — there wasn’t a Masquerade at all — there is the occasional act. In this case there are two acts. (Kylo is lending a lightsaber to Rick.) It gets a lot of attention, perhaps surprisingly given the very communalist vibe of Chinese society.

The person dressed as Kylo Ren is quick to shoo the children out of the frame so that everyone can take a picture in an orderly fashion.

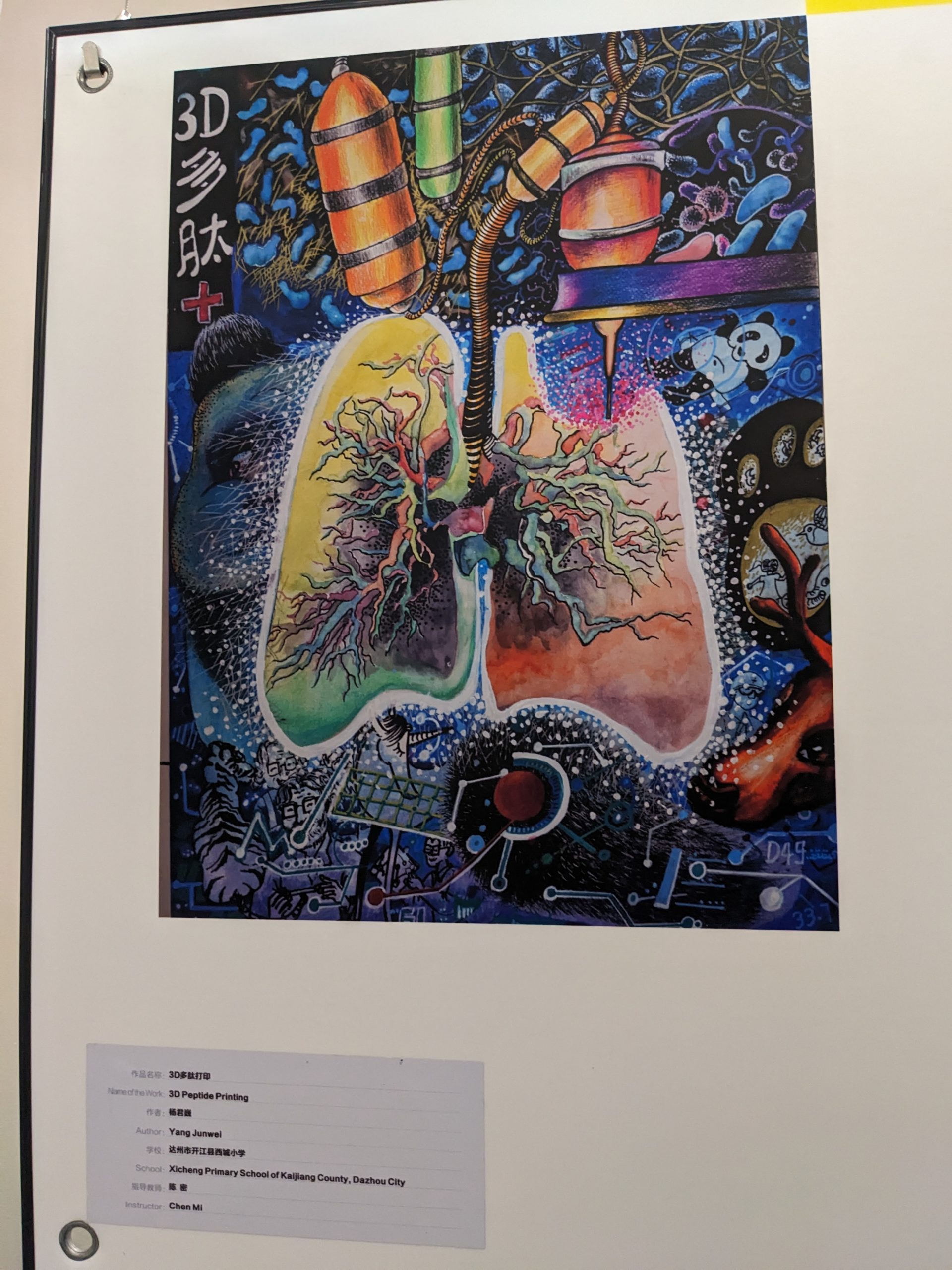

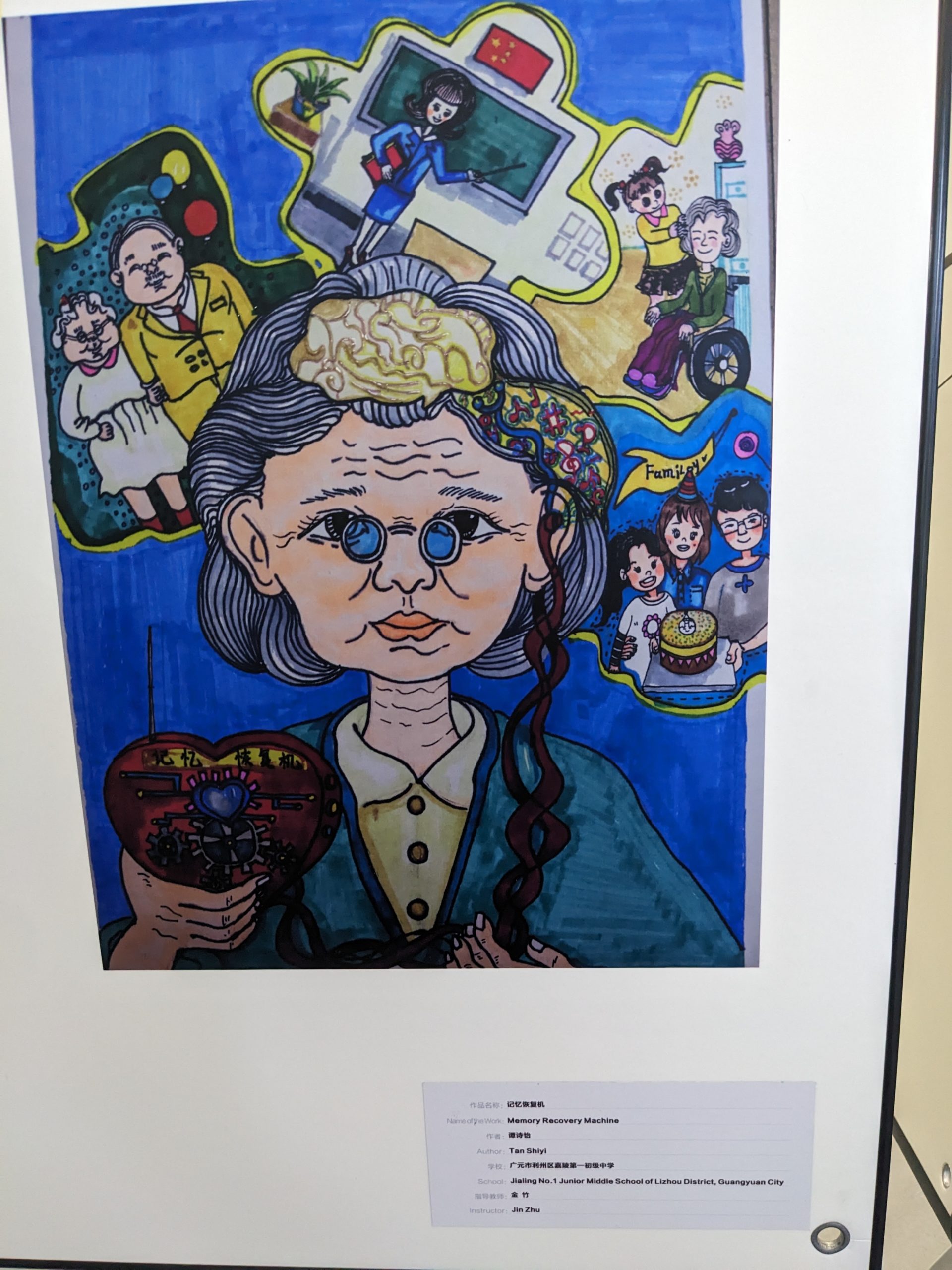

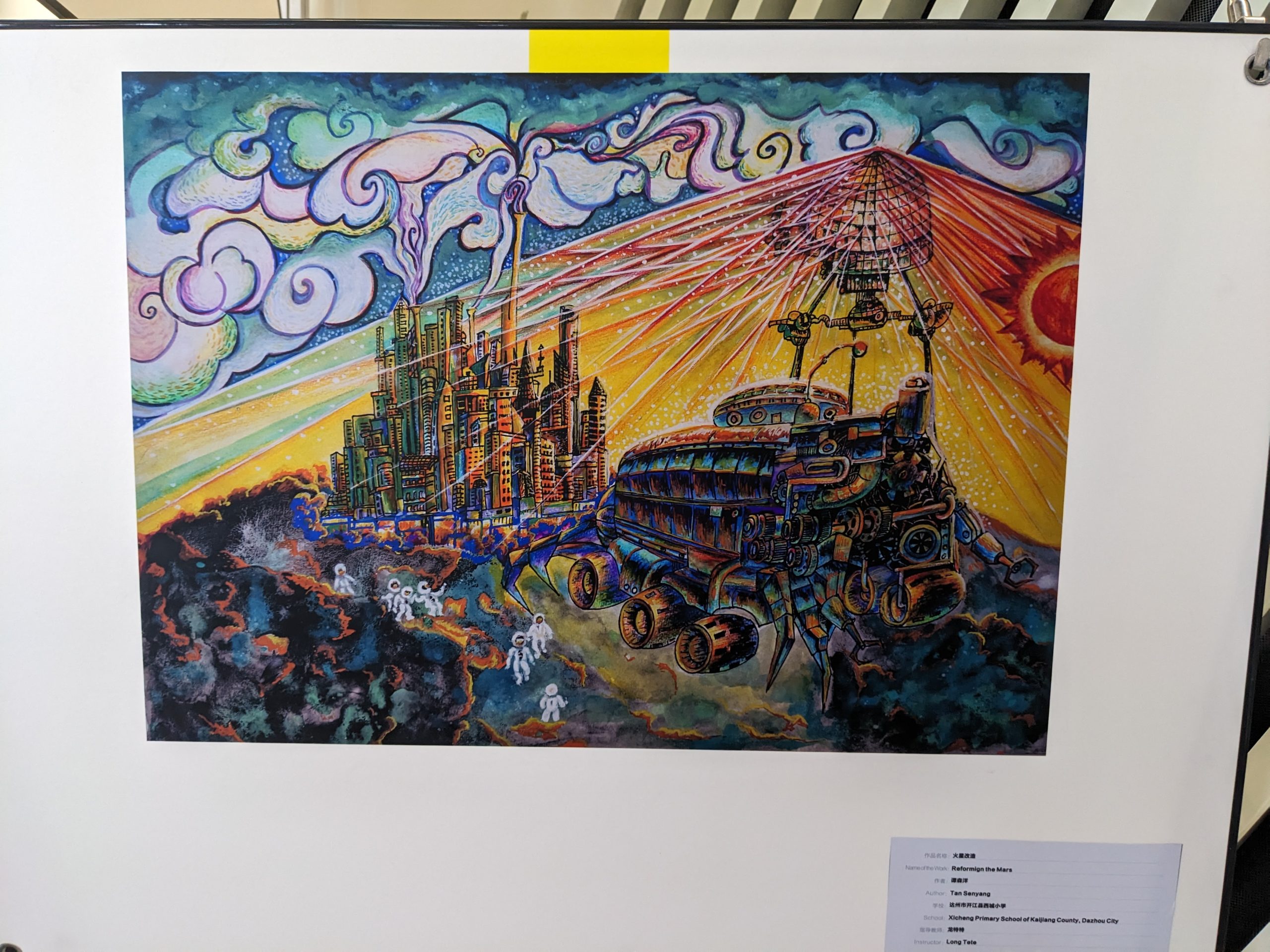

I decide that I’m going to set my mind to enjoy this convention to the extent possible, and thing I can do is to look at the different pieces of art around the convention. On the top floor is quite a bit of art from what seem like nearby schools, and although I am looking at them at first out of boredom, I find a lot to appreciate about some of them.

Some are simply wildly creative in the way that children’s work can be.

Some is legitimately incredible.

I find a few pieces whose use of color is very interesting. This one gives me van Gogh vibes.

I also pass a few other cultural encounters: garbled English on a garment, security staff chatting idly with one another, a giant model of the convention mascot which appears to serve as Instagram bait for fashionable young people and one that might be a model.

When I squeeze as much entertainment as I can out of the top floor, I wander the grounds again looking if there’s anything fun to do. I spot Tim and Sophia off in the food court area and I chat with them while they eat. Tim has just started a new job so they aren’t staying through the whole event — they are leaving tomorrow, Sunday. Back in Portland, they are very into board games and other recreational activities — Tim runs an event. It’s fascinating to hear about. I complain about the lack of a game room, but mention that I always carry Hanabi, and did they want to play? We find an area full of seating, a sort of "quiet zone" for attendees, and sit around a free table to play. We do pretty well for our first game. I am hopeful that someone will be interested in the game and come over and talk to us, but no such luck.

Then it’s time for the Hugo Awards.

They are using projectors to make this sculpture a little more interesting.

It turns out that we sit next to Rick. (Thanks Sophia for taking this picture.)

The Hugo event is pretty good, but largely what you would expect. I’m sure there’s better coverage elsewhere. "Everything, Everywhere, All At Once" wins a Hugo. There’s a presentation, as there usually is during the Hugos, of all the names of fans we’ve lost over the last year, which is set to a sad acoustic song about leaving someone behind, and I tear up a little bit. However, none of the names are Chinese.